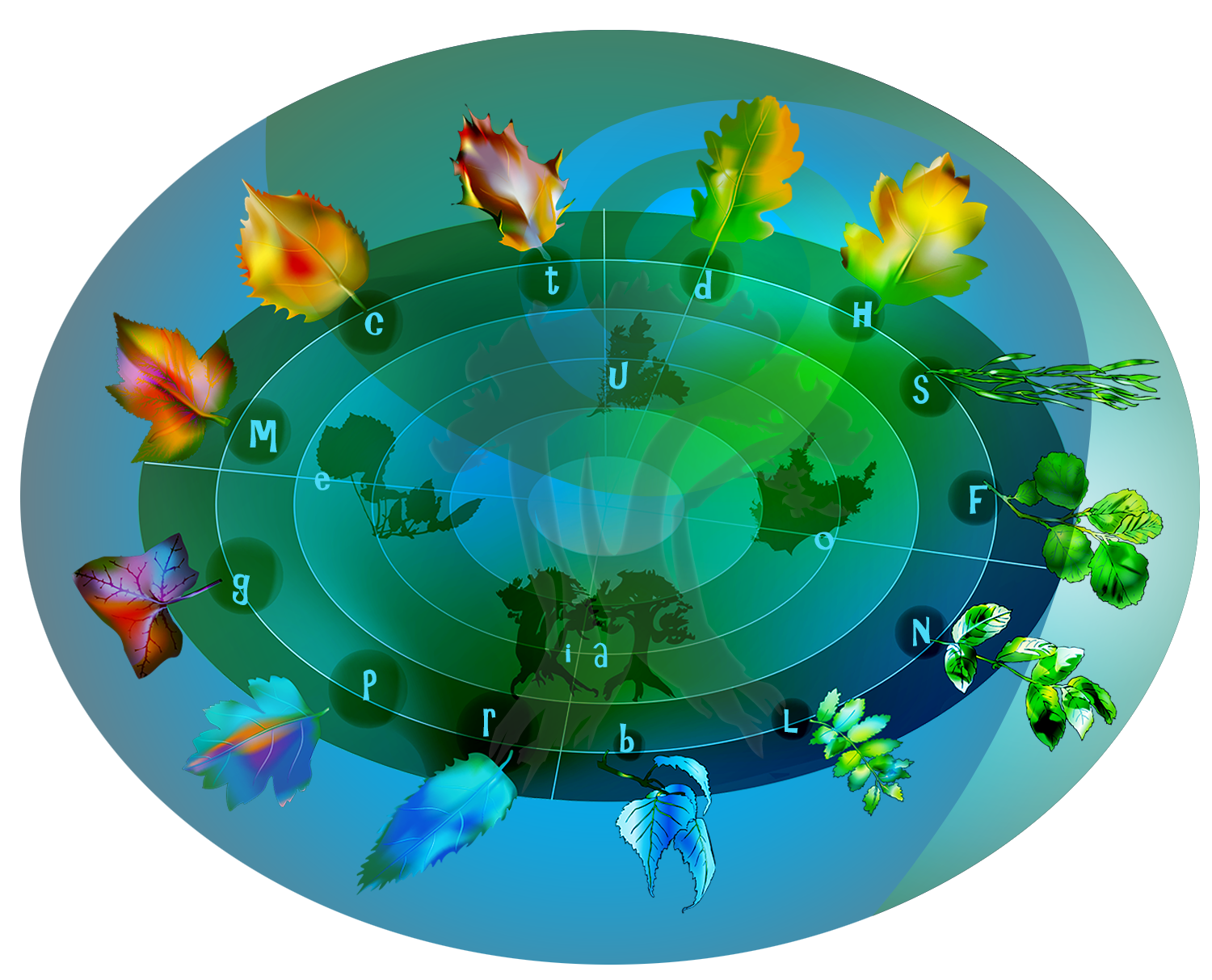

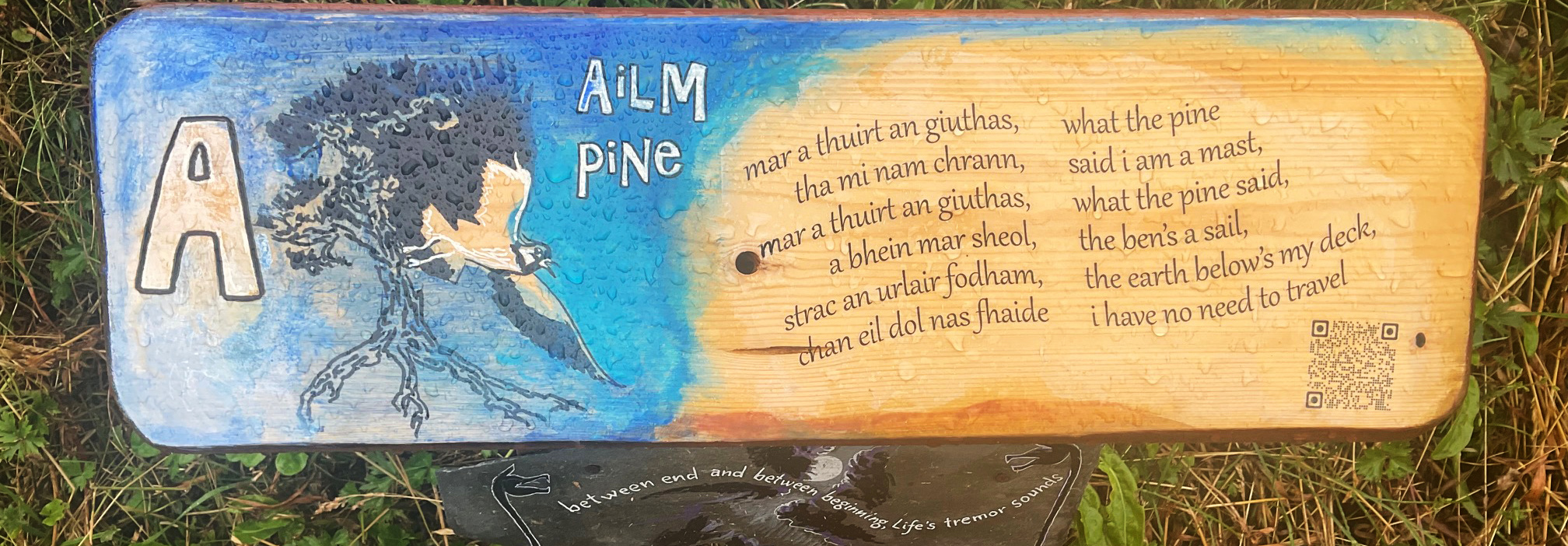

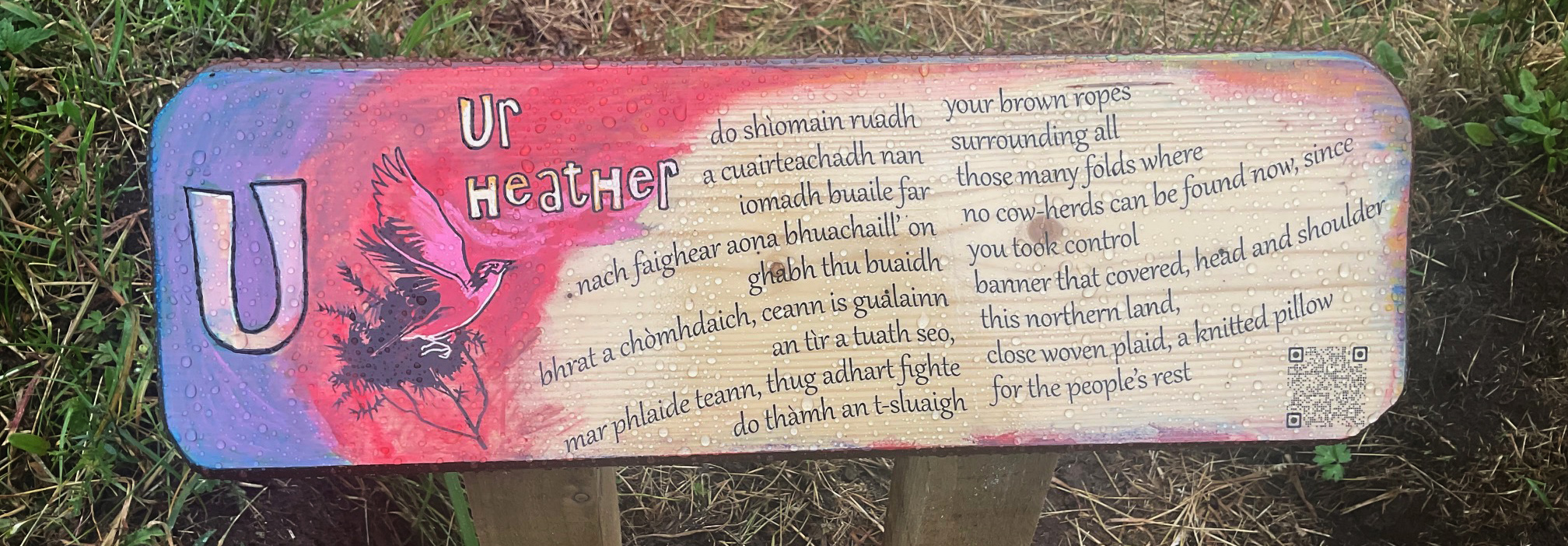

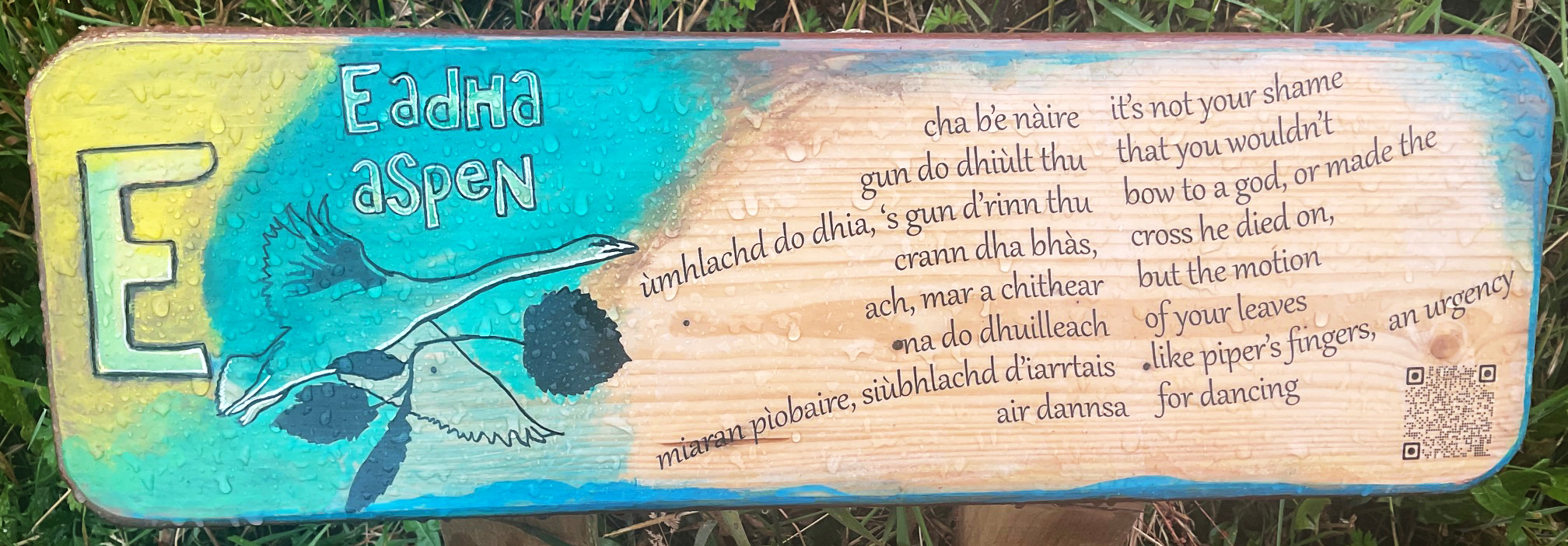

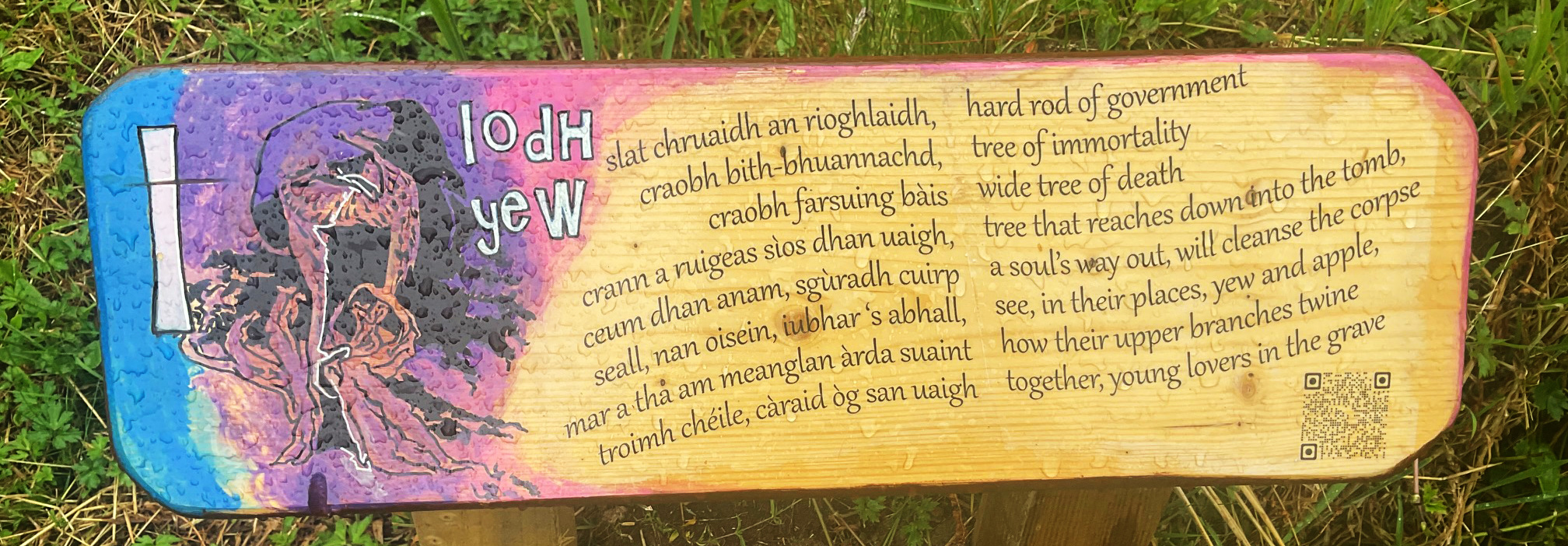

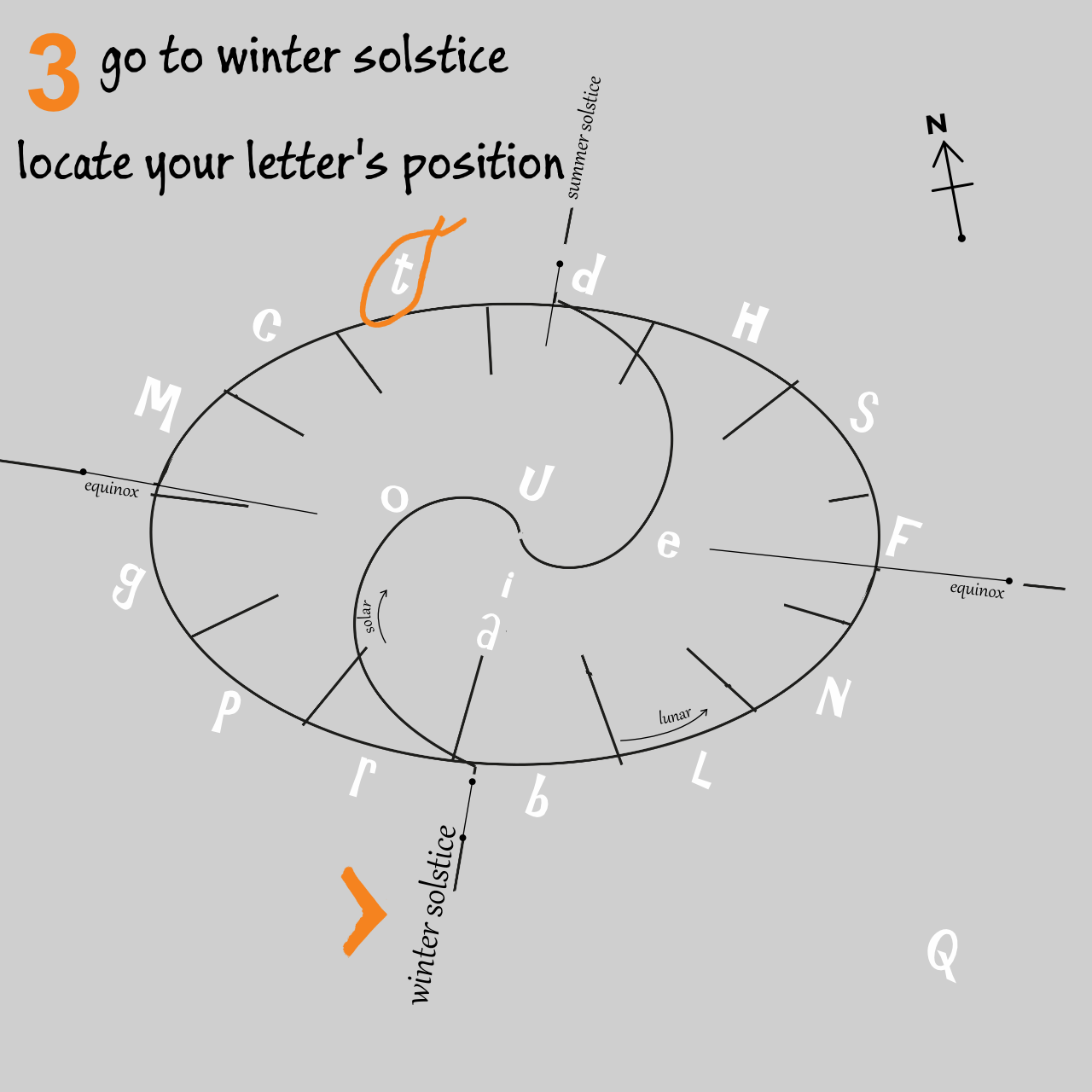

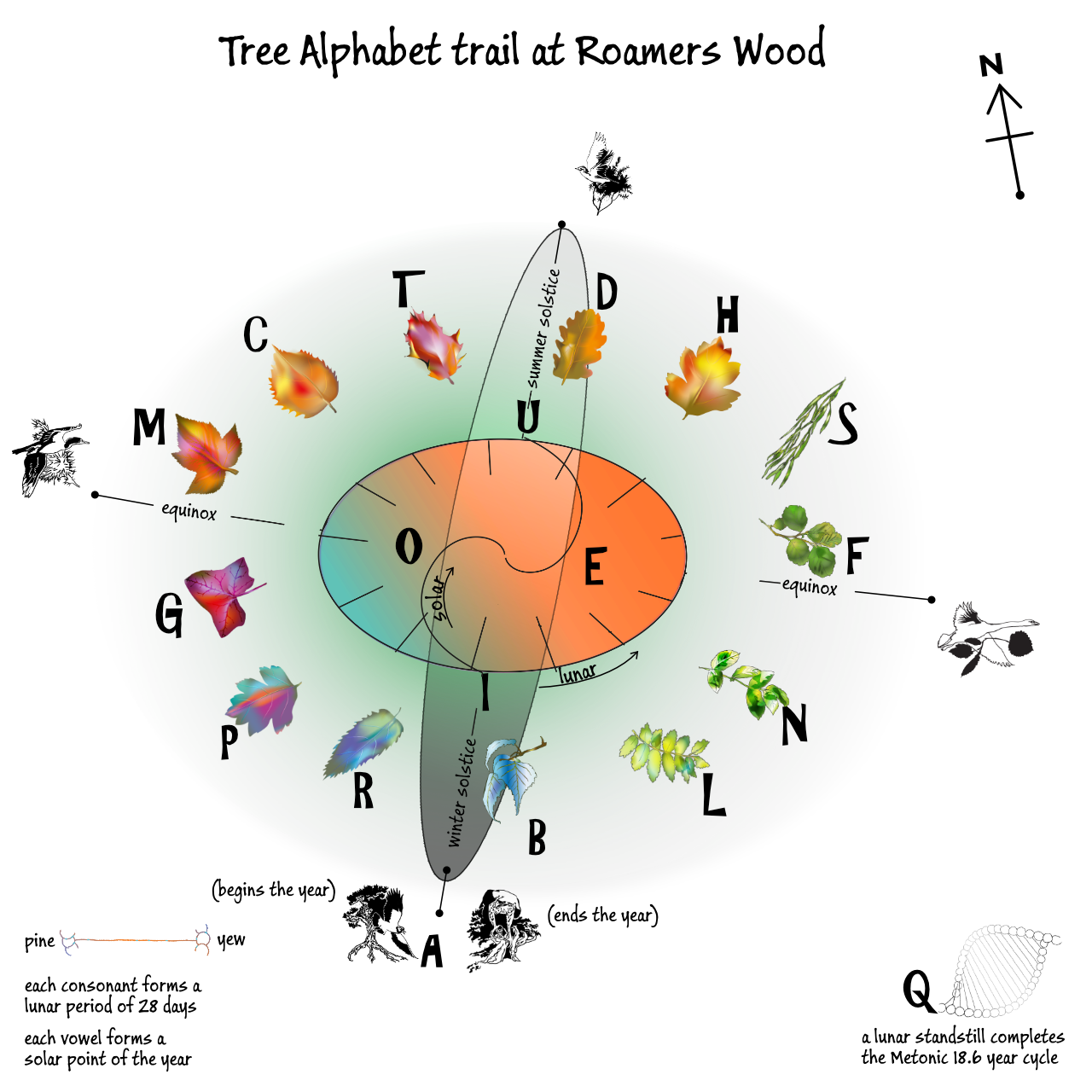

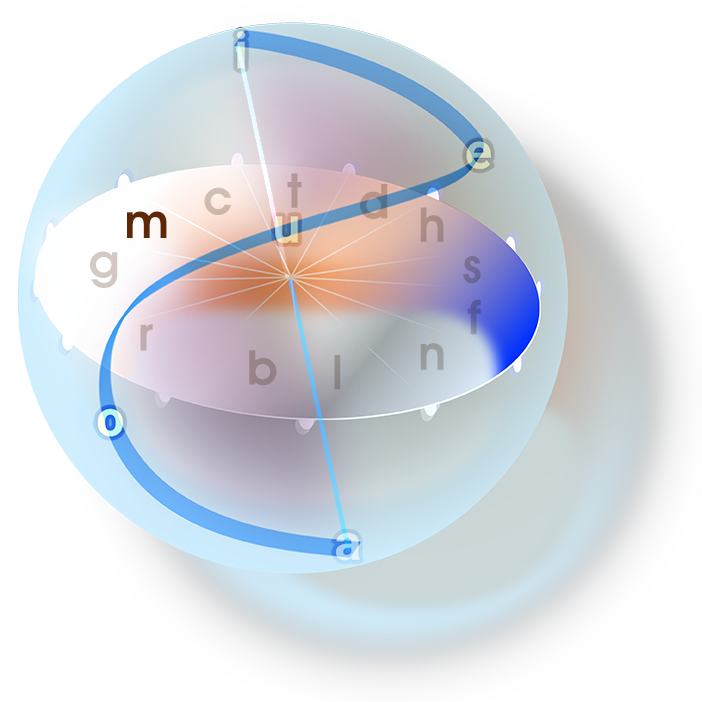

A tree alphabet arranges its nineteen tree species in an outer circle of thirteen consonants (each a lunar period of 28 days) while its five vowels form a special (“Fibonacci”) spiral, and the whole is oriented to sunrise and sunset at solstices. Each letter represents a tree species that is used as the means of memory in this ancient library.

Can you guess the names of each tree from the shapes of their leaves, and what information they might hold?

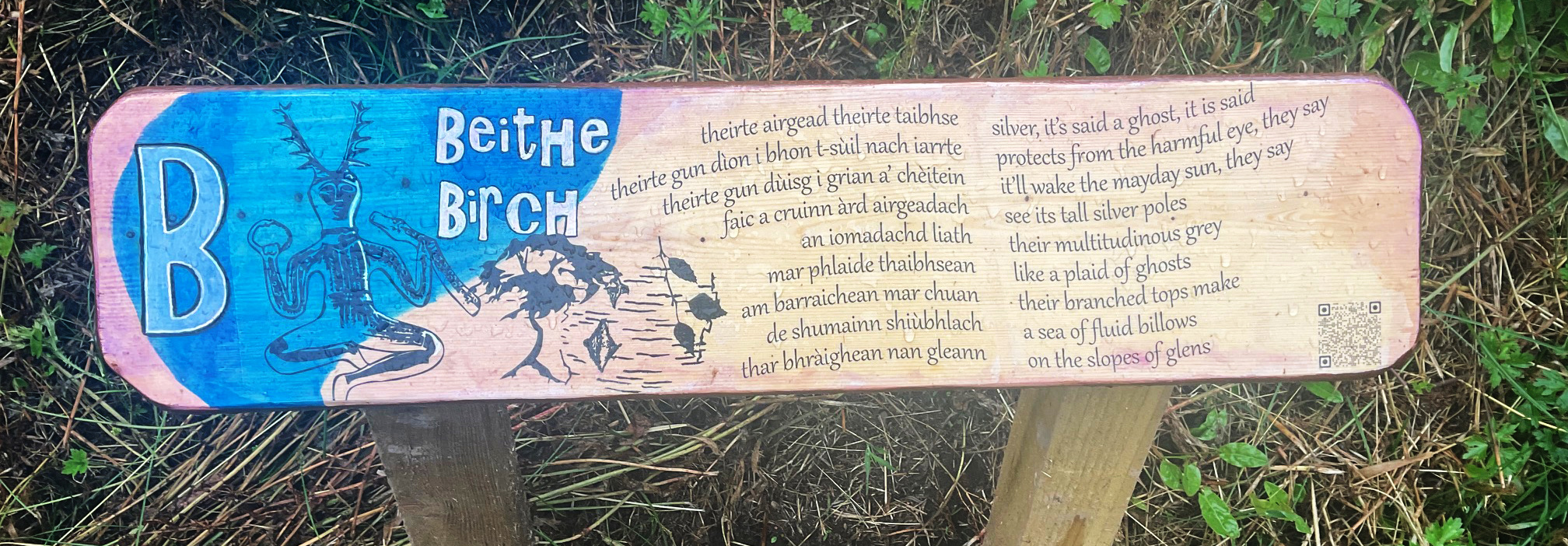

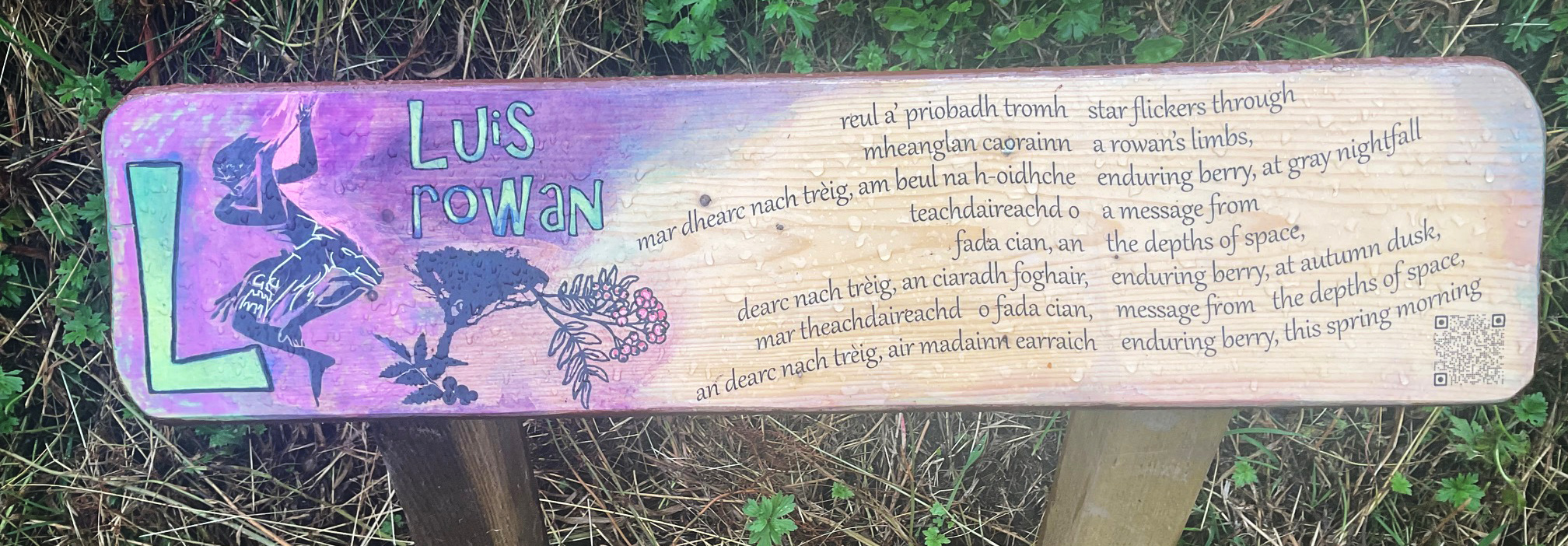

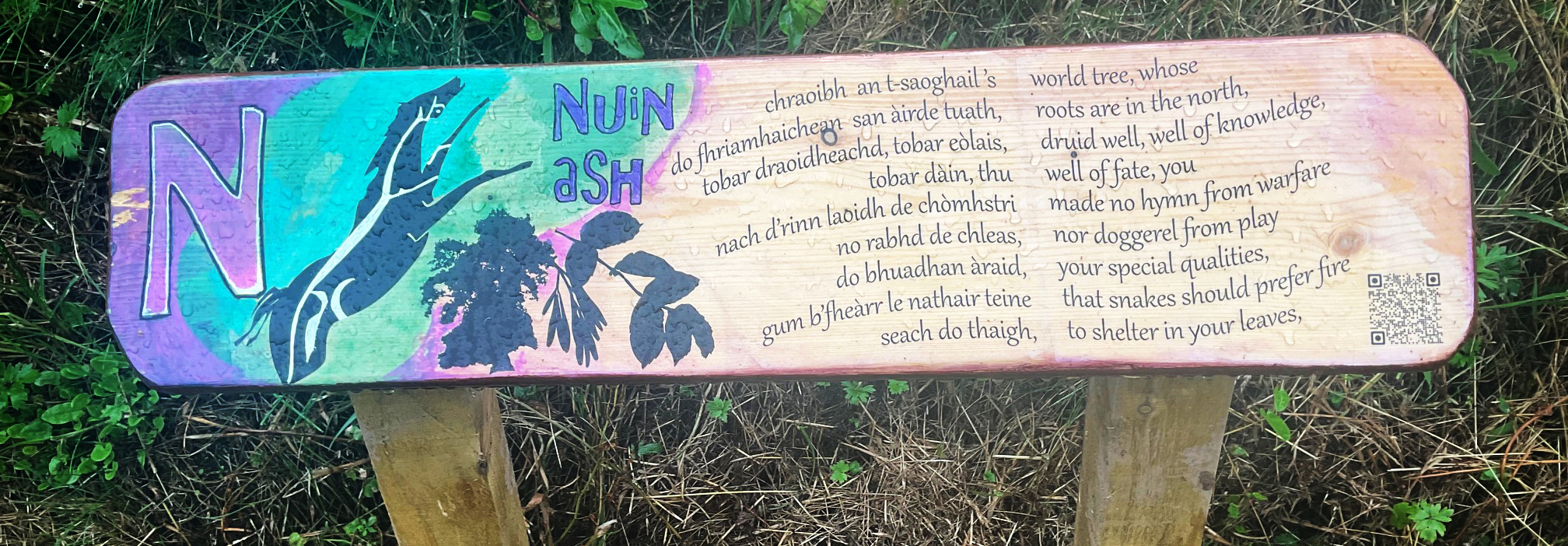

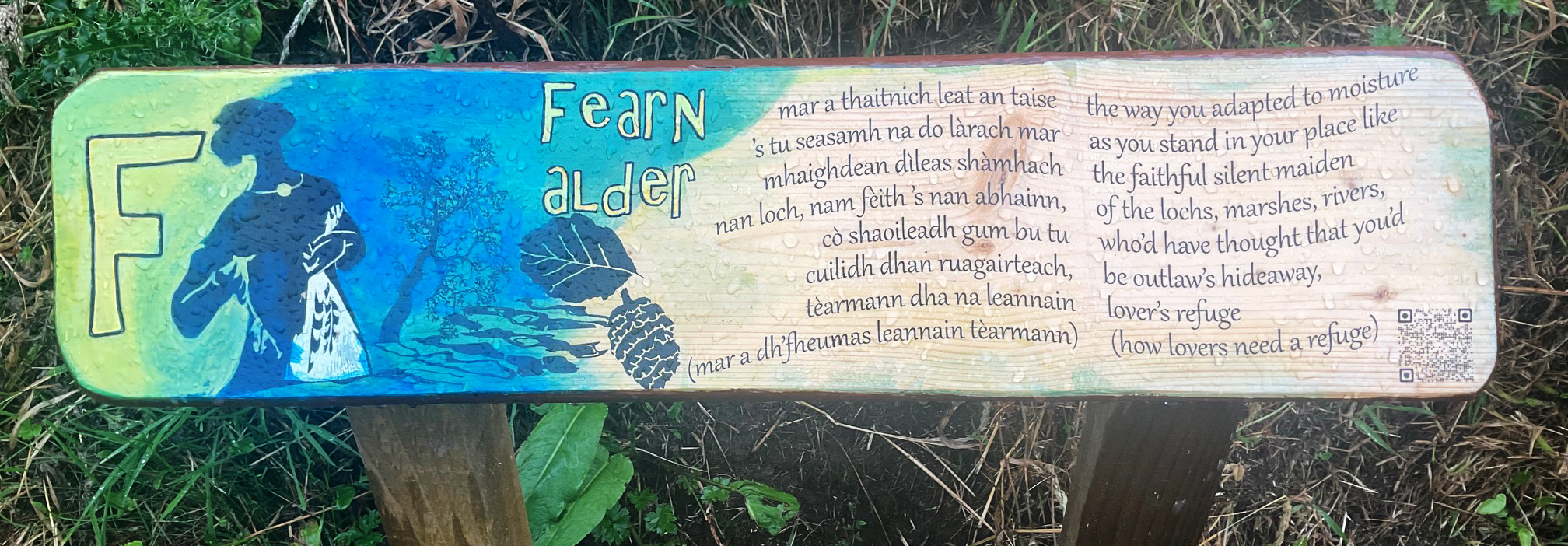

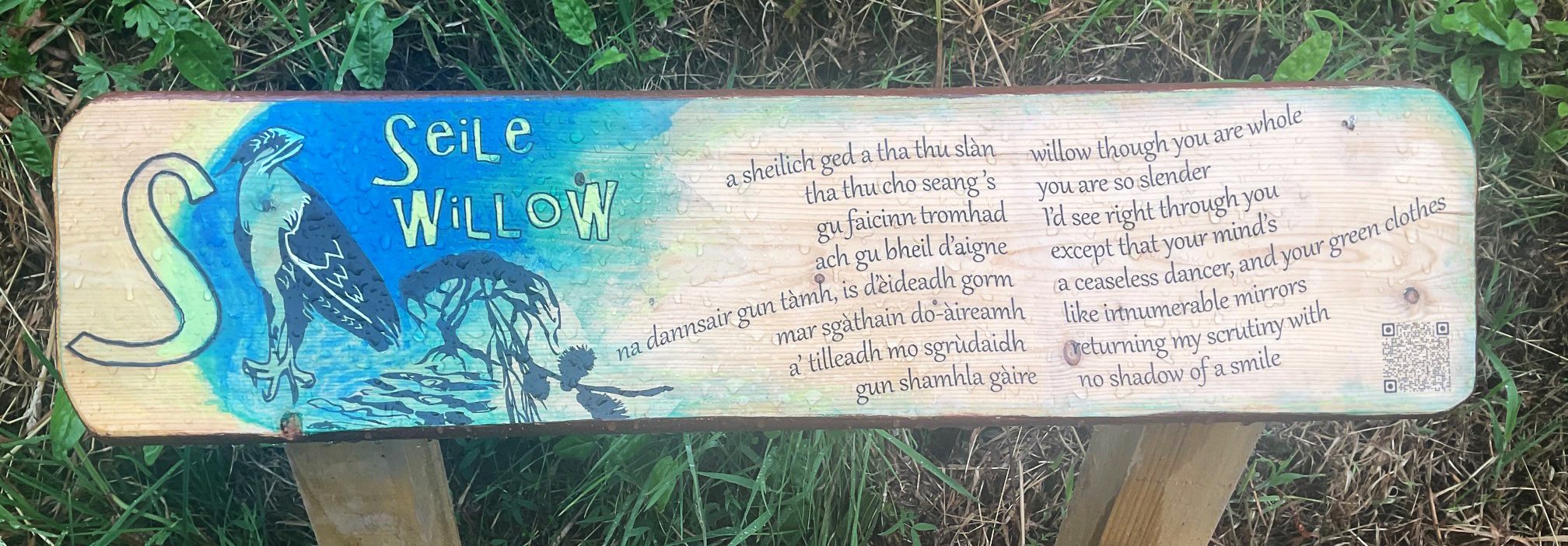

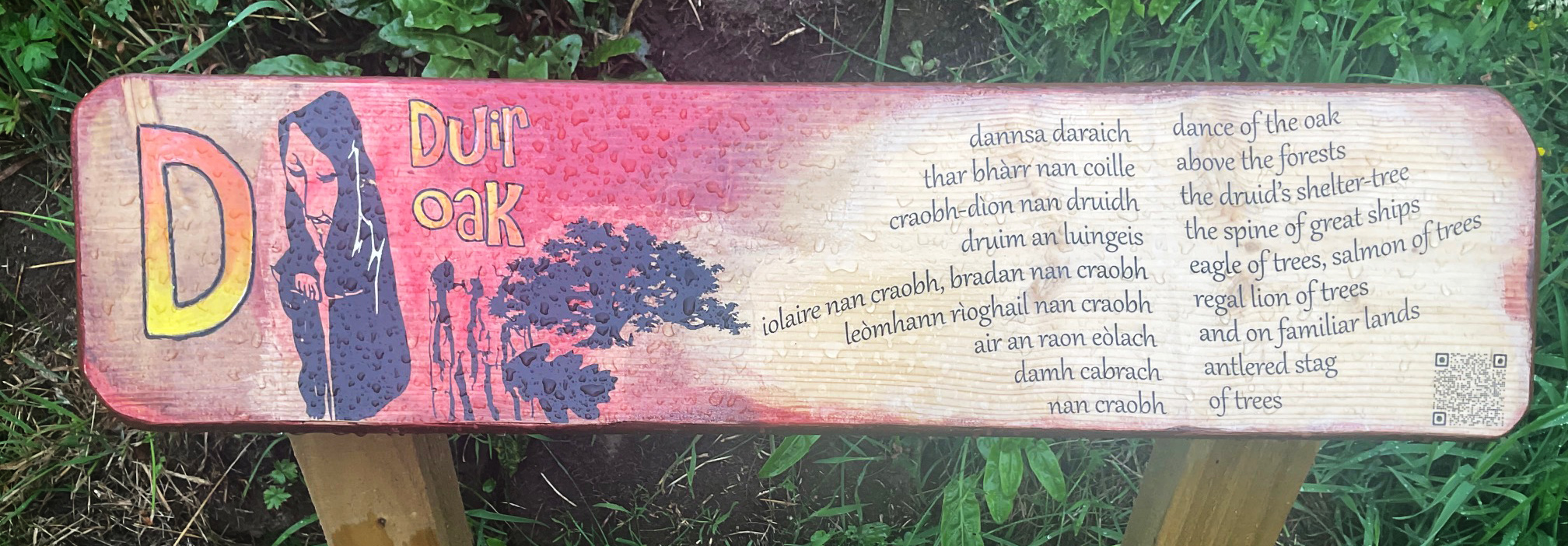

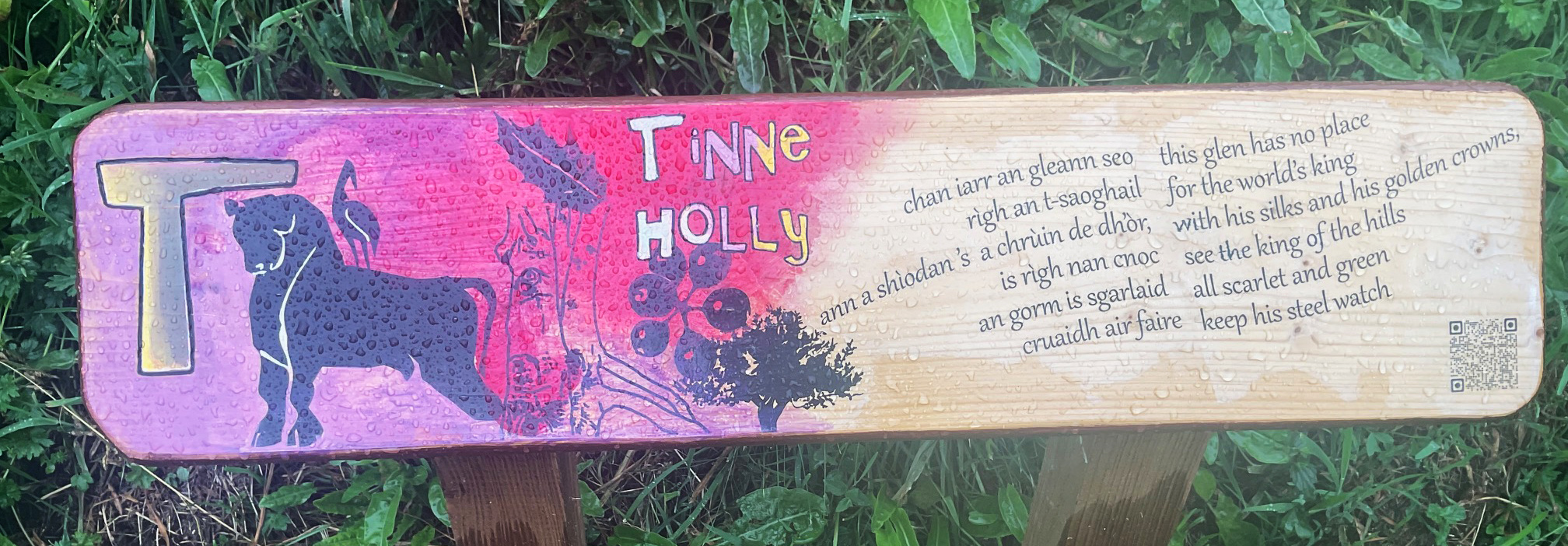

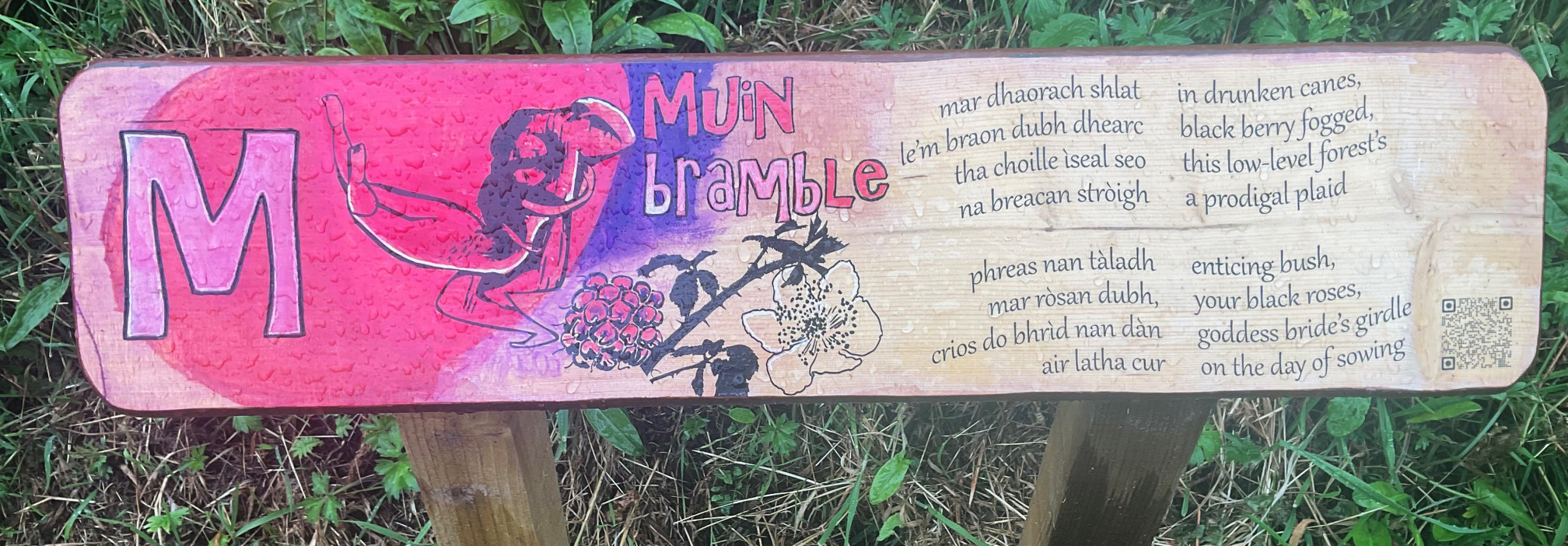

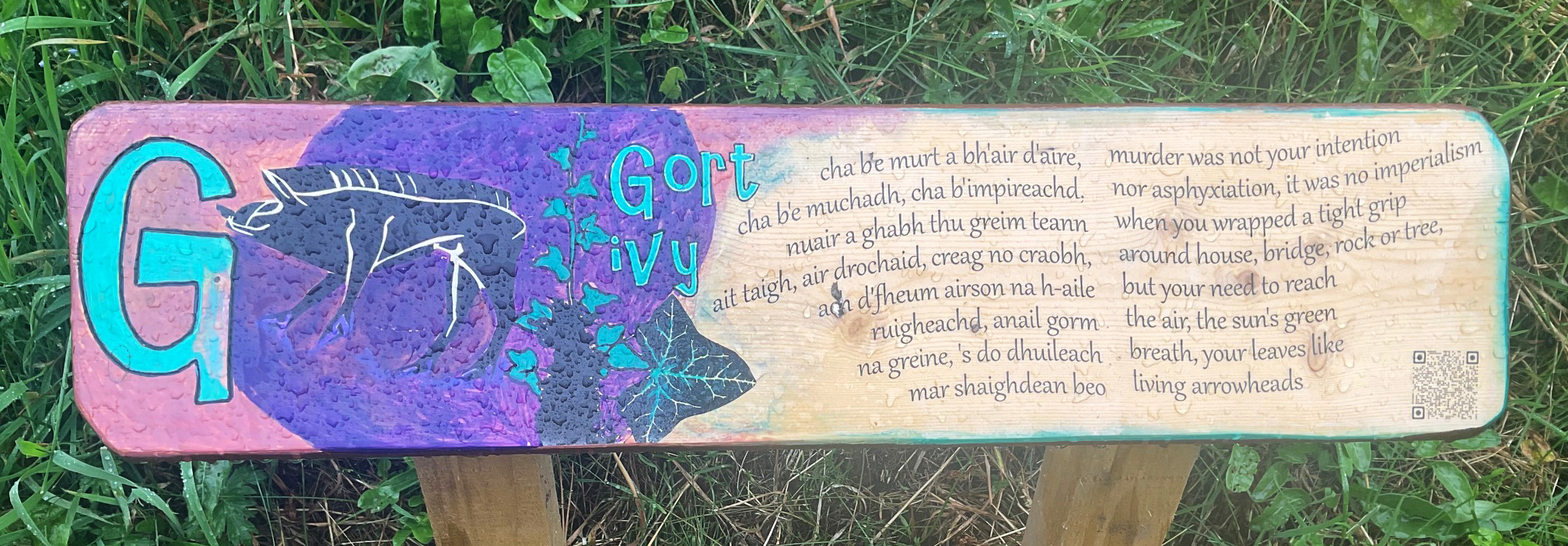

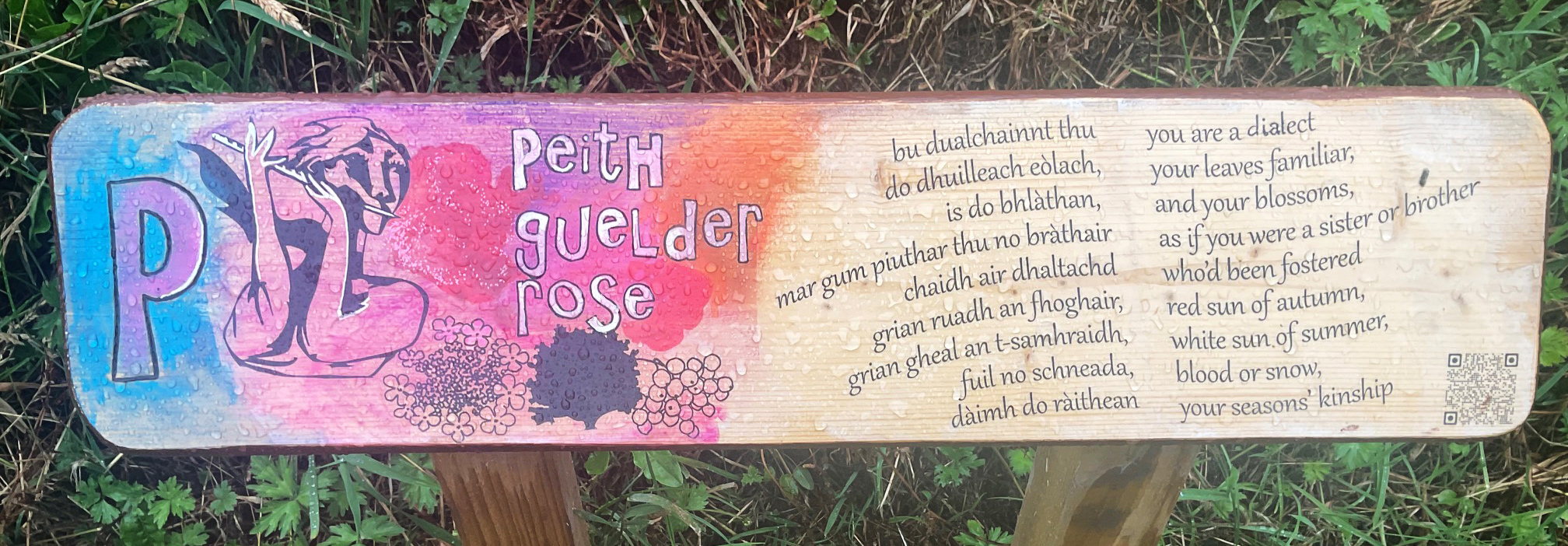

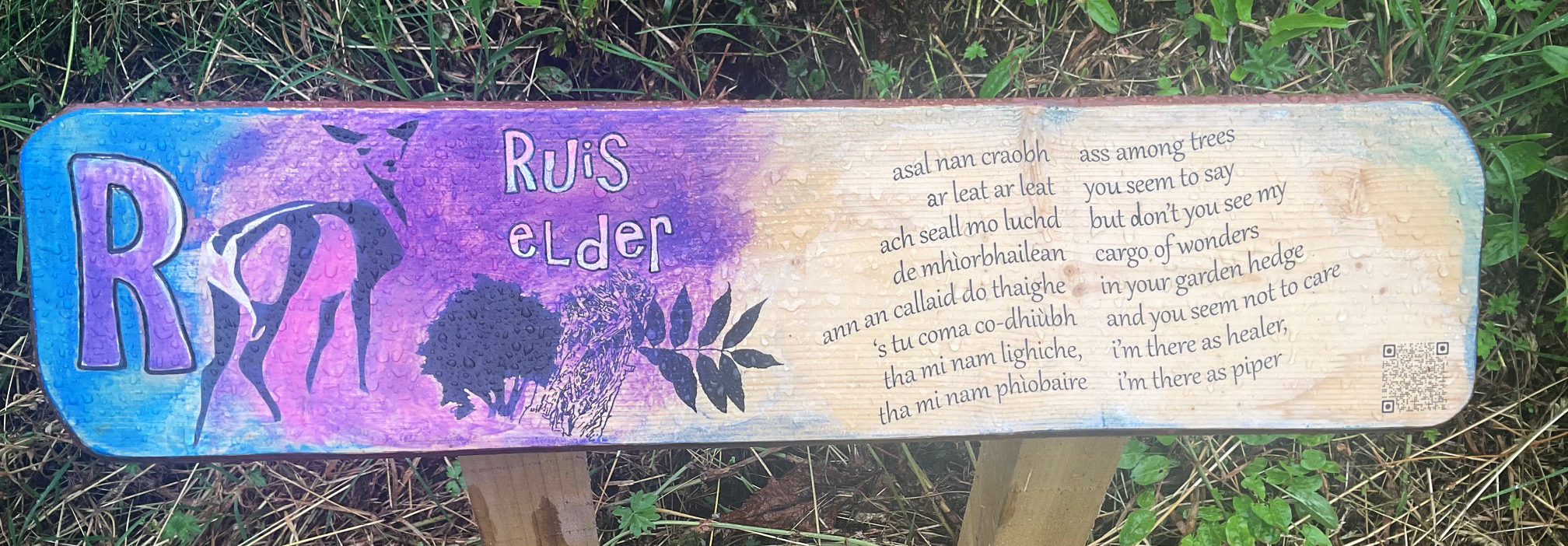

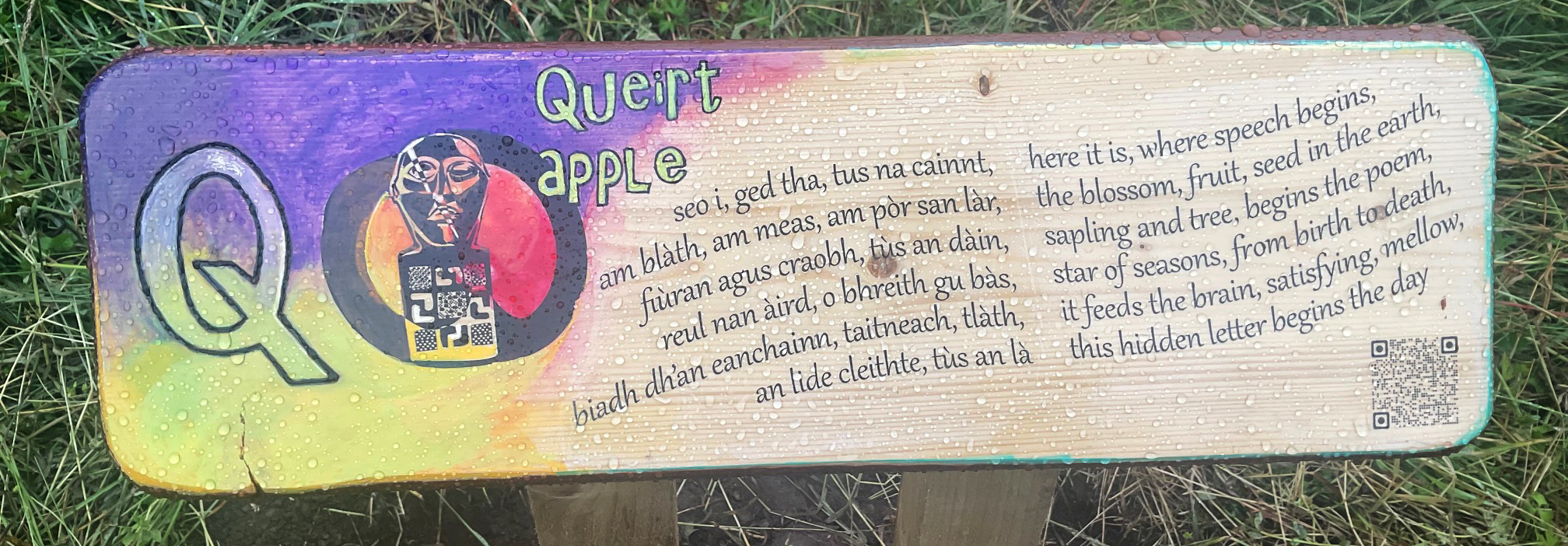

Below are the boards that have extracts of poems by Aonghas MacNeacail brought to life in audio recordings by Rob MacNeacail and with graphics by Simon Fraser.

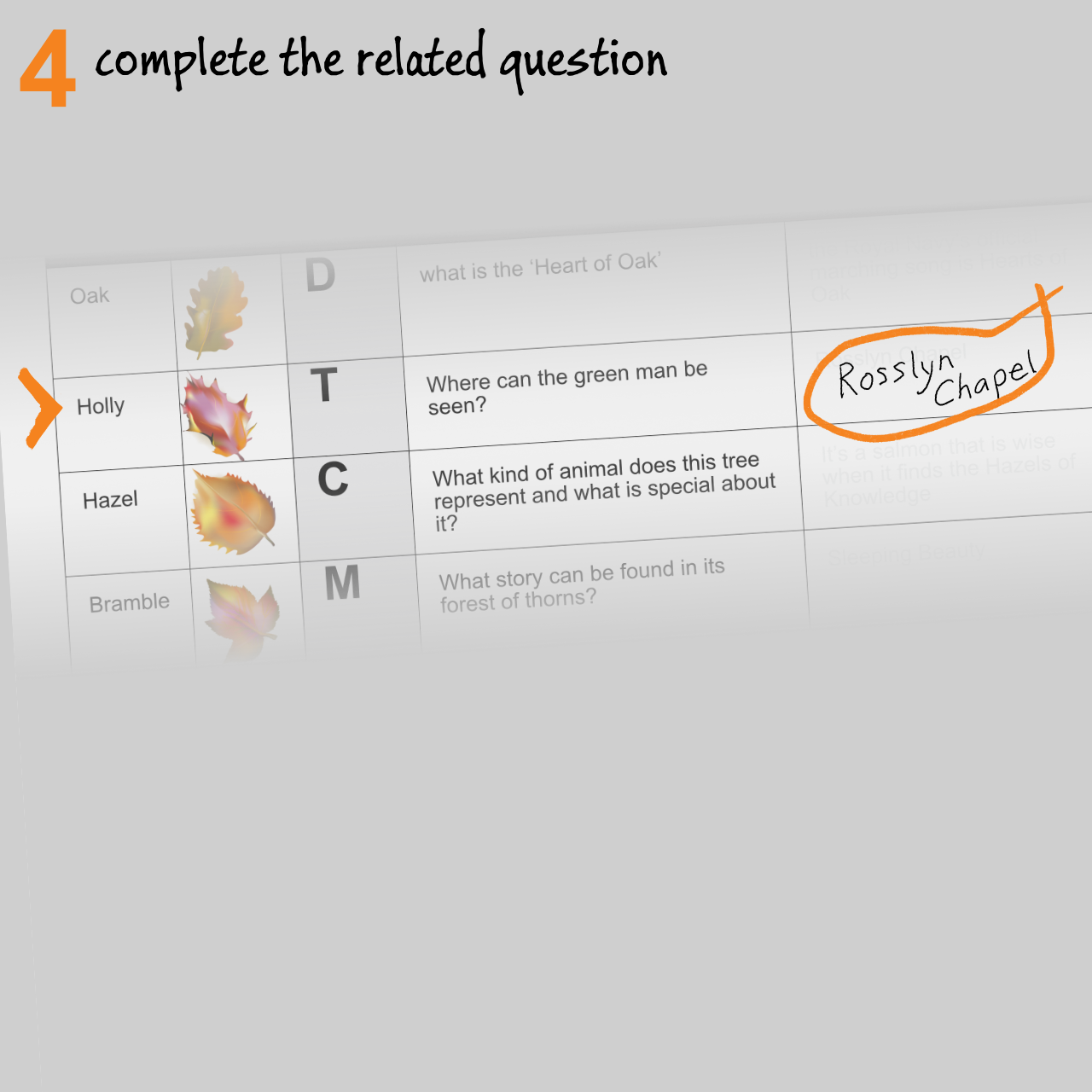

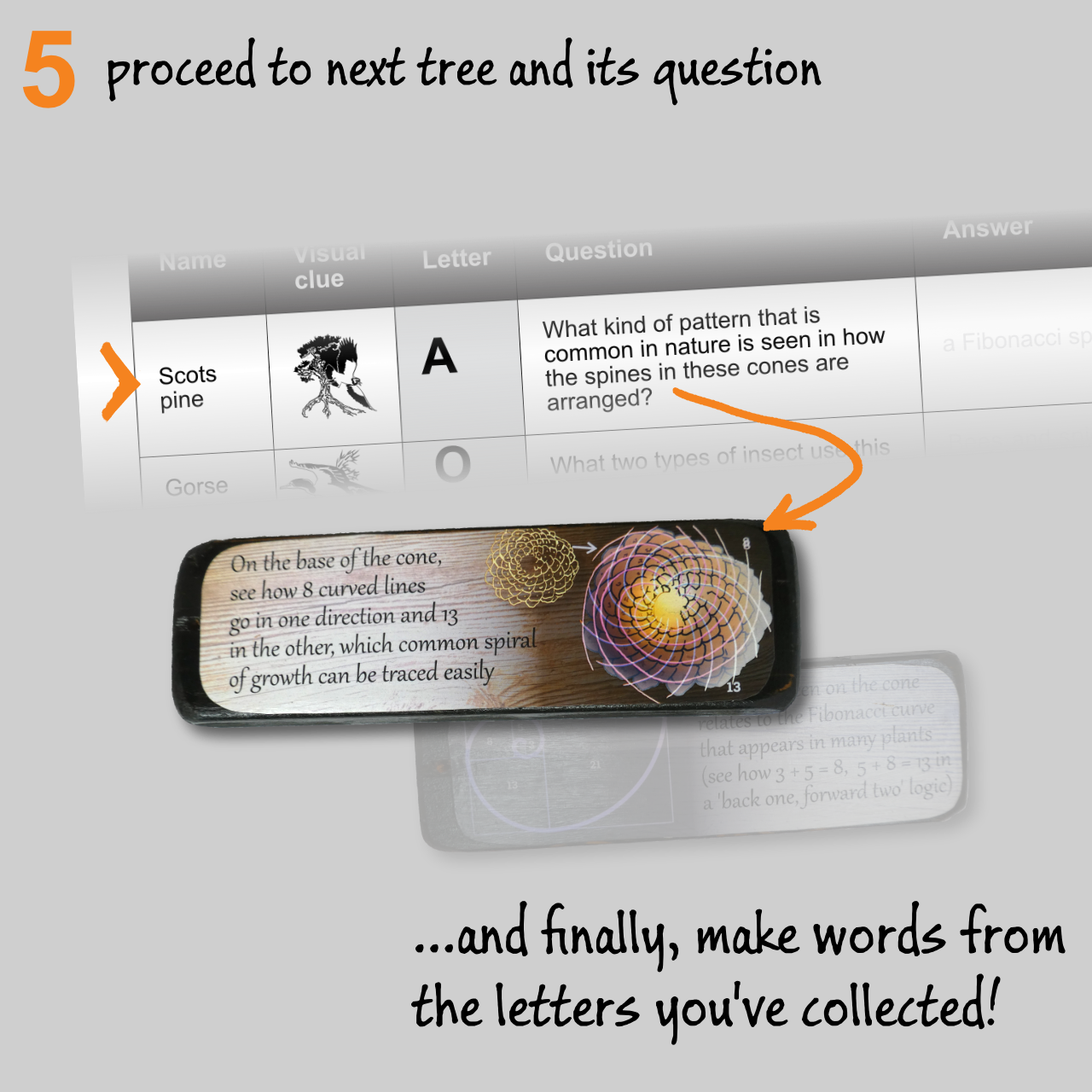

A simple hunt that P7 have done that follows a trail of clues. (images can be enlarged)

Curious to learn more about the Celtic tree alphabet? Then visit here

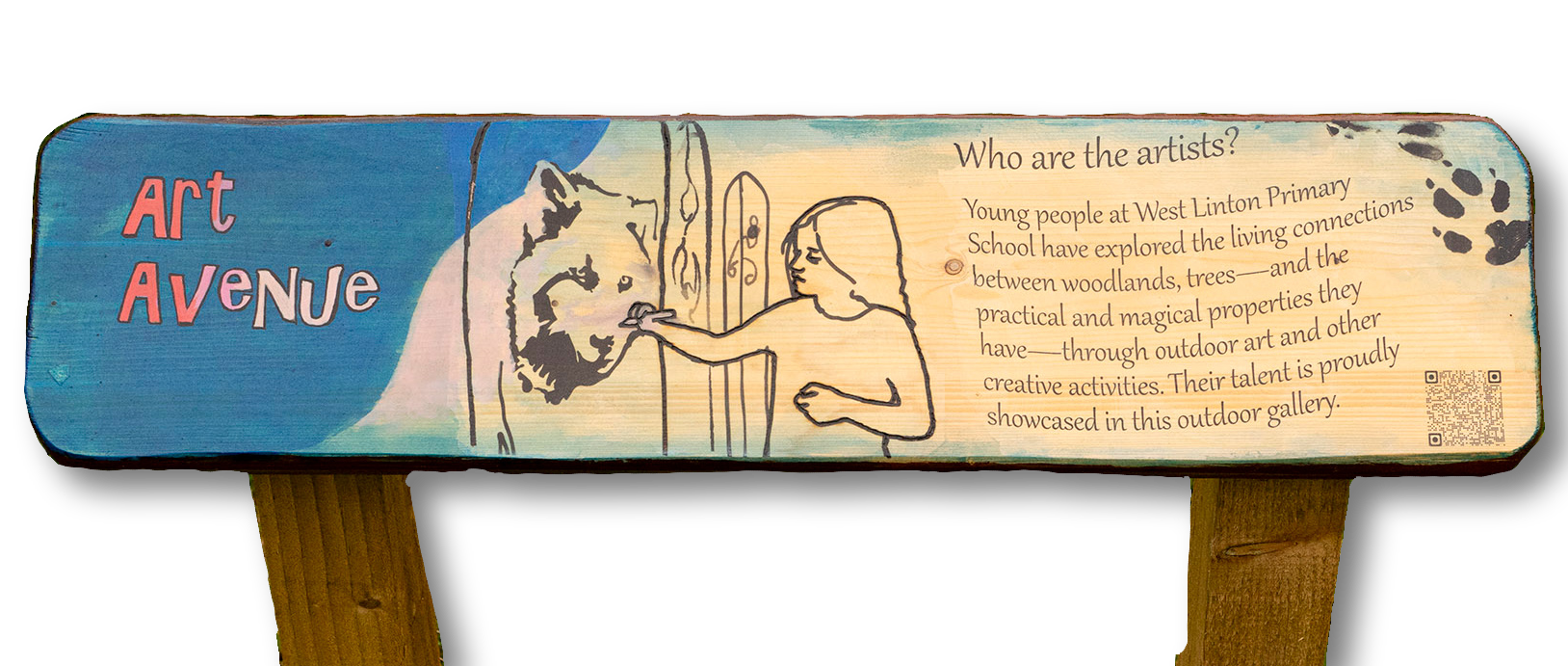

Pupils from West Linton Primary School regularly visit Roamers Wood for outdoor learning activities covering curriculum topics crucial to their understanding of the natural environment. In parallel, pupils have created artwork inspired by their responses to these visits. This fabulous work is now on display in situ along an ‘Art Avenue’ at Roamers Wood. The displays are still developing and but everyone is encouraged to visit and admire the pictures

These pictures provide a flavour of what the pupil have been up to, from cave art to cyanotype prints to tree spirits to decorating homes for wildlife and more. Roamers Wood is fast becoming a unique and valuable outdoor resource.

these are some examples of slates by the children taken by Angel Shan

these are some examples of slates by the children taken by Angel Shan

a few example slates by the children

a few example slates by the children

Behind the four calendrical points of Imbolc, Beltane, Lughnasadh and Samhain lie parallel 'tree stories' that map to sap, solar, fruit and fungi correspondencies within trees, and these parallels are well captured in the 2,000 year old Gundestrup Cauldron, a silver heirloom whose forgotten lore still beautifully illustrates the hidden turning points within trees. This forms the reason for the cauldron being referenced here.

The graphics here are based on the Gundestrup Cauldron, a silver heirloom once buried in a Danish bog. Its meanings and reason for burial are debated, however, as metaphor for the 'calendrical earth-science' of its day it remains a wonderful pointer to earth and tree lore, each with seasonal significance.

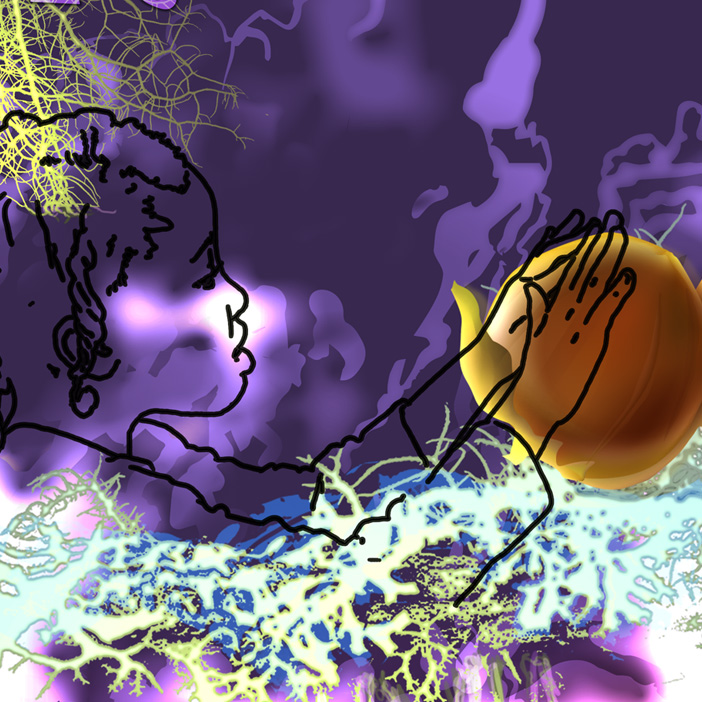

As herald to the year to come, Imbolc symbolises the stirring of life once more with hidden movements out of sight, beneath foot and root and bark.

Long celebrated as Brigit (or Brig or Brigde in the Tuatha Dé Danann) and later as St Brigid, she is consistently the goddess of birth, wisdom and poetry.

On the Gundestrup Cauldron she is shown with her hair being braided, a striking metaphor for the weave of mycorrhizal purpose in the inter-threading of lives.

Similarly, her supportive hold of man and beast awaiting their rebirth, as well as bird in her hand... the synonym of beauty in earth-lore.

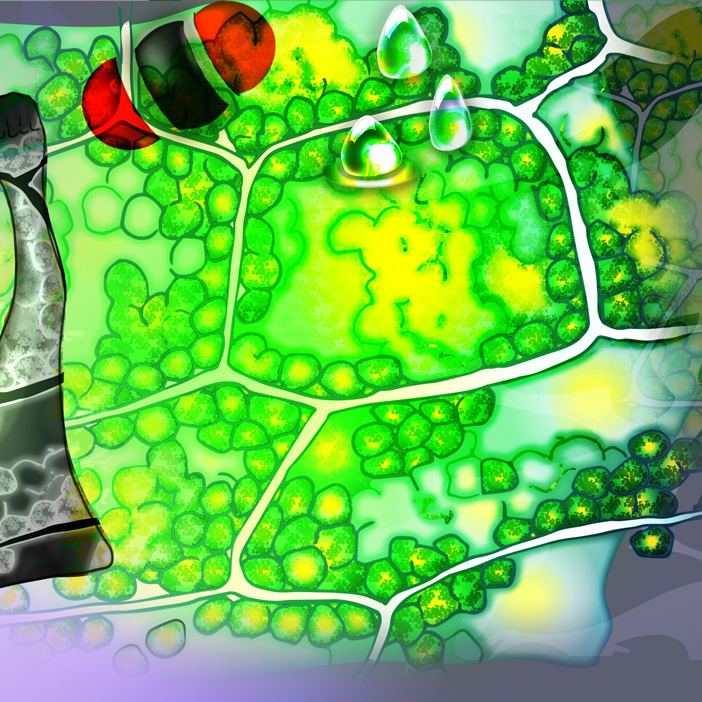

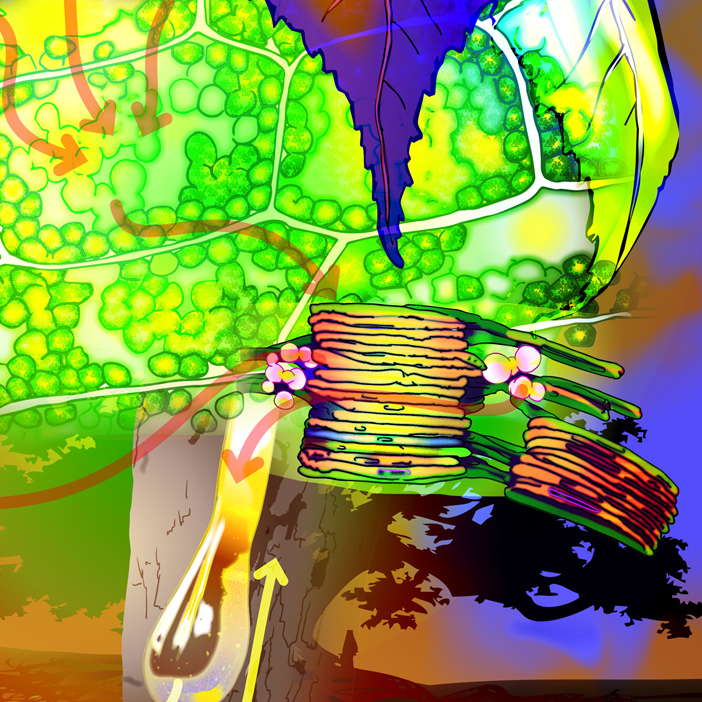

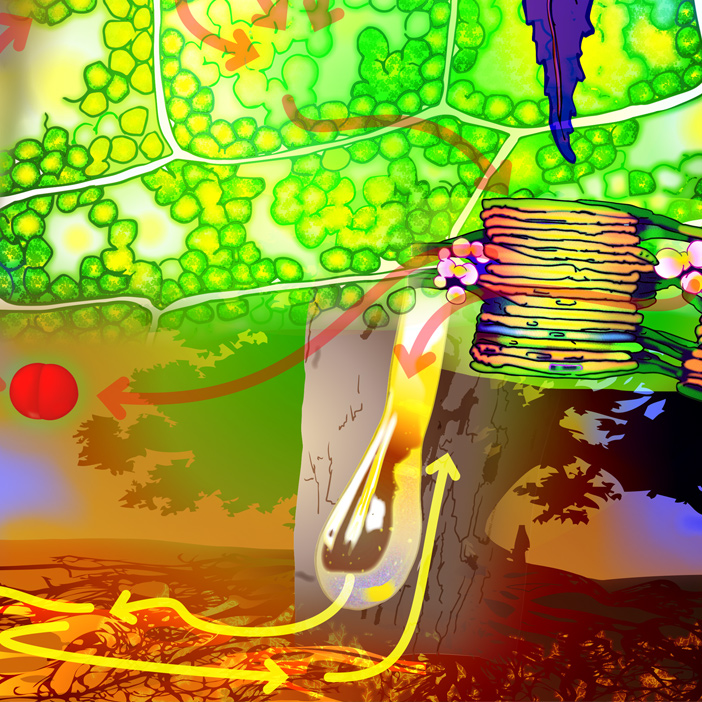

Beltane (meaning the fire/teine of Bel) on May Day, has been celebrated as dance for thousands of years, yet it also symbolises a dance now at its peak in leaf.

Here in the leaf, chloroplasts wriggle madly to a green dance as they enfold carbon-dioxide, water and sunlight.

At the centre of this dance within each chloroplast, are thylakoids who perform a 300 million year old trick.

Their ancient chemical trick is similar to our solar panels, in which sunlight is converted into energy (sap) and oxygen released into the air.

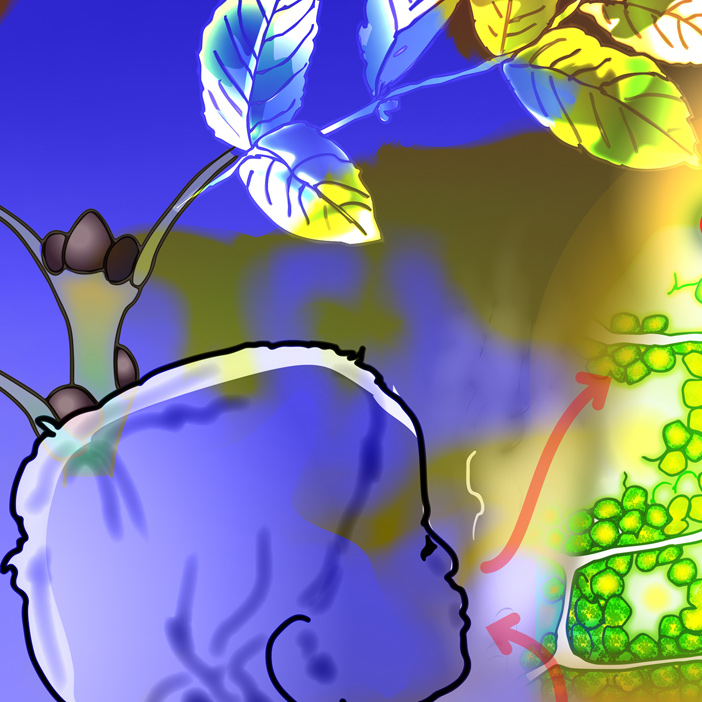

In August begins the vital season for harvest of fruit and nut.

This collection period was once hugely critical, and in Lughnasadh (the 'assembly of Lug') lay many hopes and fears.

Lug was warrior king, craftsman and holder of justice, very much the keeper of this subtle balance at harvest time.

And the Druidic tradition of 'keeper of the woods' extends directly from this.

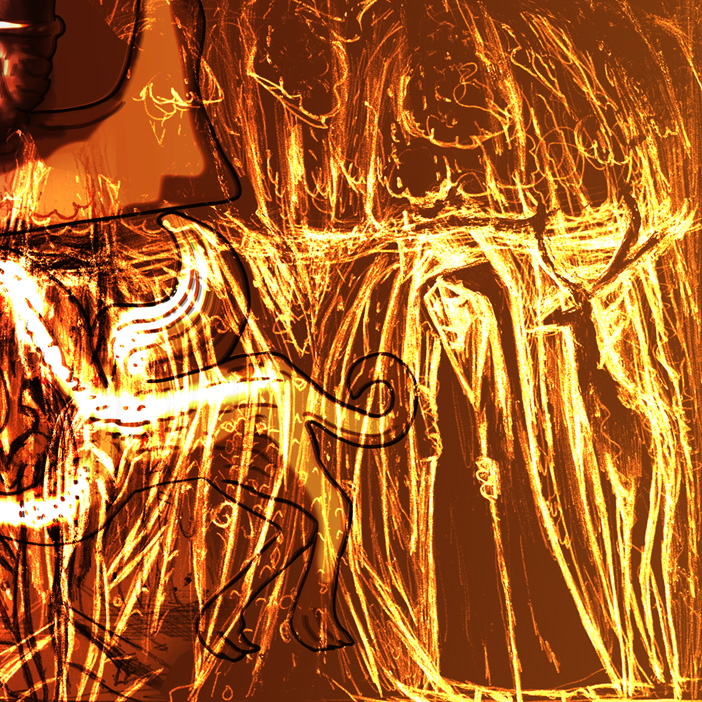

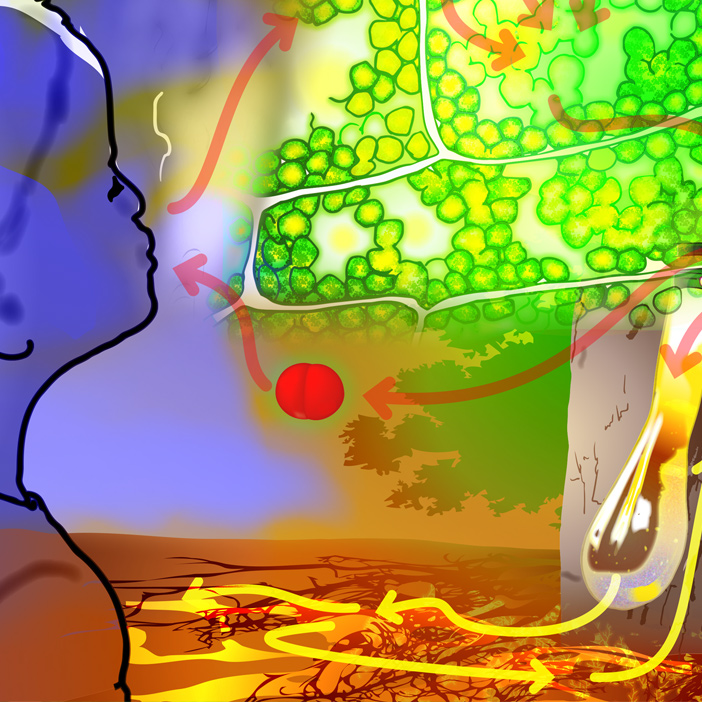

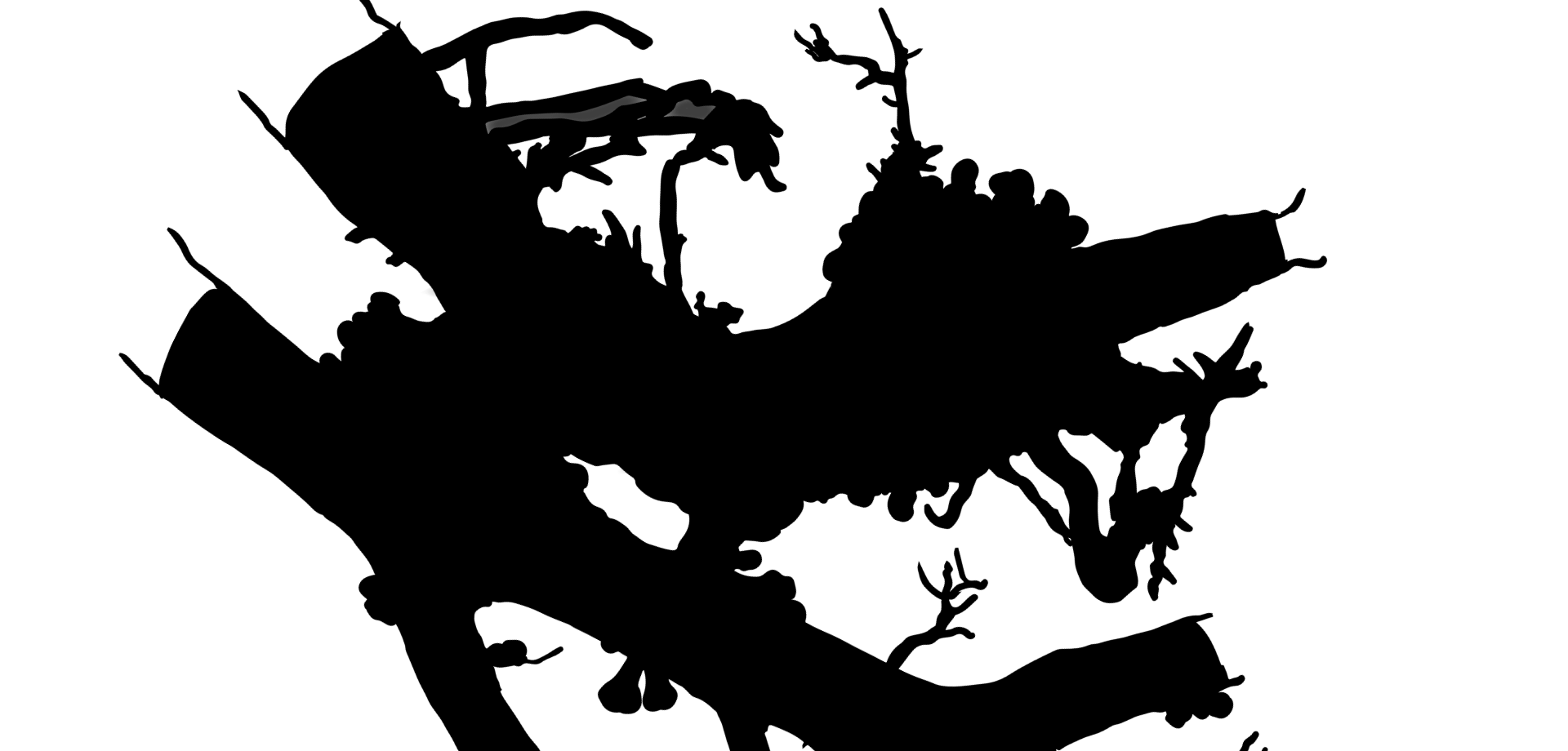

At Samhain (Halloween) and Nov 1st, a glimpse into the underworld is a common thread in the old stories where Cernunnos holds sway over life and rebirth.

In many of them, two worlds can be seen at once at the interchange of death and life.

In ancient procession, as old as time, life descends downward through half remembered wayleaves to begin new lives.

Where the carnyx, once heard across vast distances, heralds entry to this heaving underworld where rebirth can begin through its vast world of microbes and so much else.

The carbon-dioxide you exhale may be used by leaves.

For within every leaf are millions of tiny green spots, the chloroplasts, that need only carbon dioxide, sunlight and water to work.

As within each chloroplast are what look like curious stacks of joined circles, called thylakoids.

A natural magic occurs on the skin of the thylakoids, where a chain reaction of chemicals takes place continuously.

This chemical chain reaction changes sunlight, water and carbon-dioxide into sap (glucose), releasing the oxygen.

The sap then travels down the tree and oxygen is released into the air

The sap that reaches the ground is exchanged in the tree roots via the fungi (mycorrhizae) for water and minerals, which then go back up the tree.

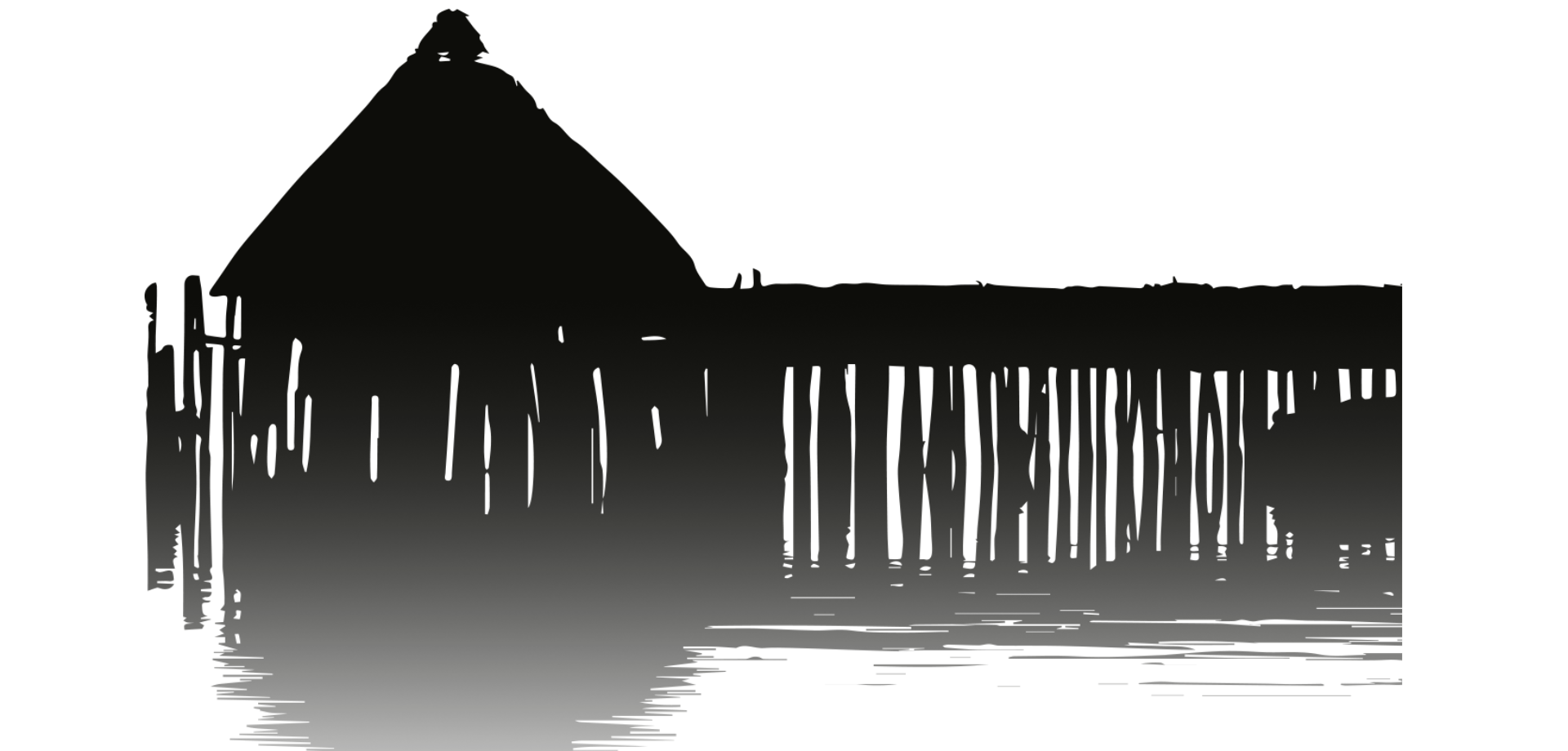

Whilst the long term aim of constructing an Iron Age roundhouse remains on the horizon, the properties of trees and their countless differences in touch, look and behaviour suggests that the best route forward is through practice with making some of them, a path that inevitably leads into folklore, a flavour of which is touched on here...

(text for above to come soon and will add useful refs such as) Crannog Centre (very relevant to building in Roamers) and Chiltern Open Air Museum (with long experience in roundhouses) and a video of a Bronze Age roundhouse (built at Butser in Wiltshire) or see how TA Outdoors build an Iron Age roundhouse in twelve days

Because alder strengthens, drains and ventilates soil, it protects wetlands from becoming marshland. Alder has small horizontal sap pustules, and the freshly cut sap is orange-red, like blood. Most durable when constantly wet, alder wood has been in use for centuries to create bridges, pumps, sluices and piles (for causeways across marshes and to support buildings). Older still are the crannogs - built in Neolithic times.

Alder leaves appear after the flowers, and are sticky to begin with (hence its latin name glutinosa). The male catkins hang down like the birch (alder belongs to the birch family), while the female catkins mature into dark woody cones, sometimes called wattles, that often stay on the tree during the winter while the winged nutlets, using tiny air bags, fly or float away on the water to germinate downstream.

The answer to the old riddle of "what can no house ever contain?" was simply "the piles on which it is built". This refers to the fact that houses long ago depended on alder. Crannogs were built on alder piles and indeed ancient cities, including Venice. Bog alder or ‘scottish mahogany' is excellent for chairs due to long immersion in bog.

Alder roots grow deeply into wet ground, binding soggy soils that other trees cannot survive in because of a lack of oxygen. This binding protects river banks from eroding therefore, and the alder also achieves this by fixing nitrogen in its roots through a bacteria (frankia alni) that form large knots in the roots as well as from the air, which is why ground under alders is often covered in black leaves in autumn (a sign of nitrogen) when this mineral is given back to the plants around it.

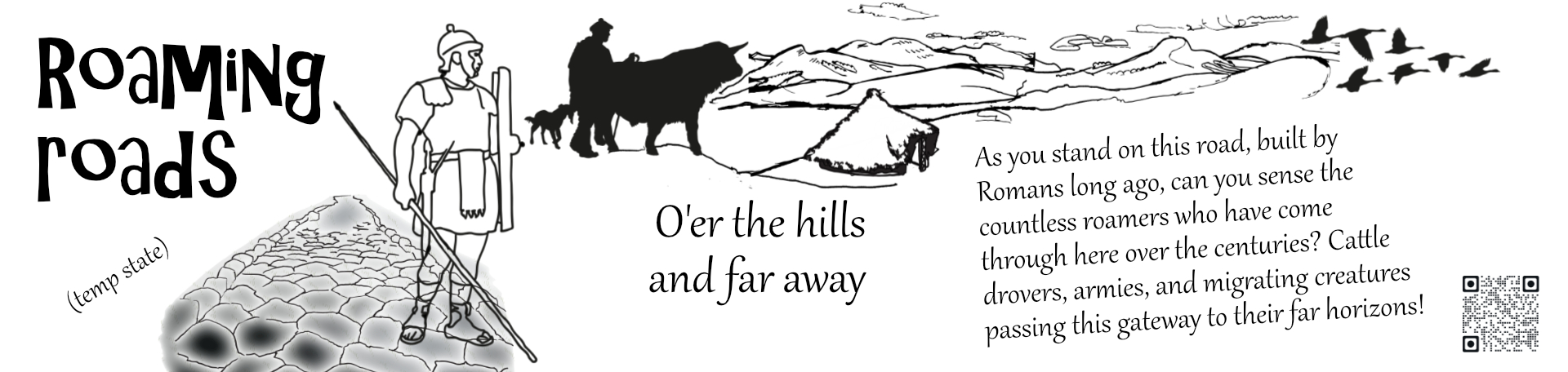

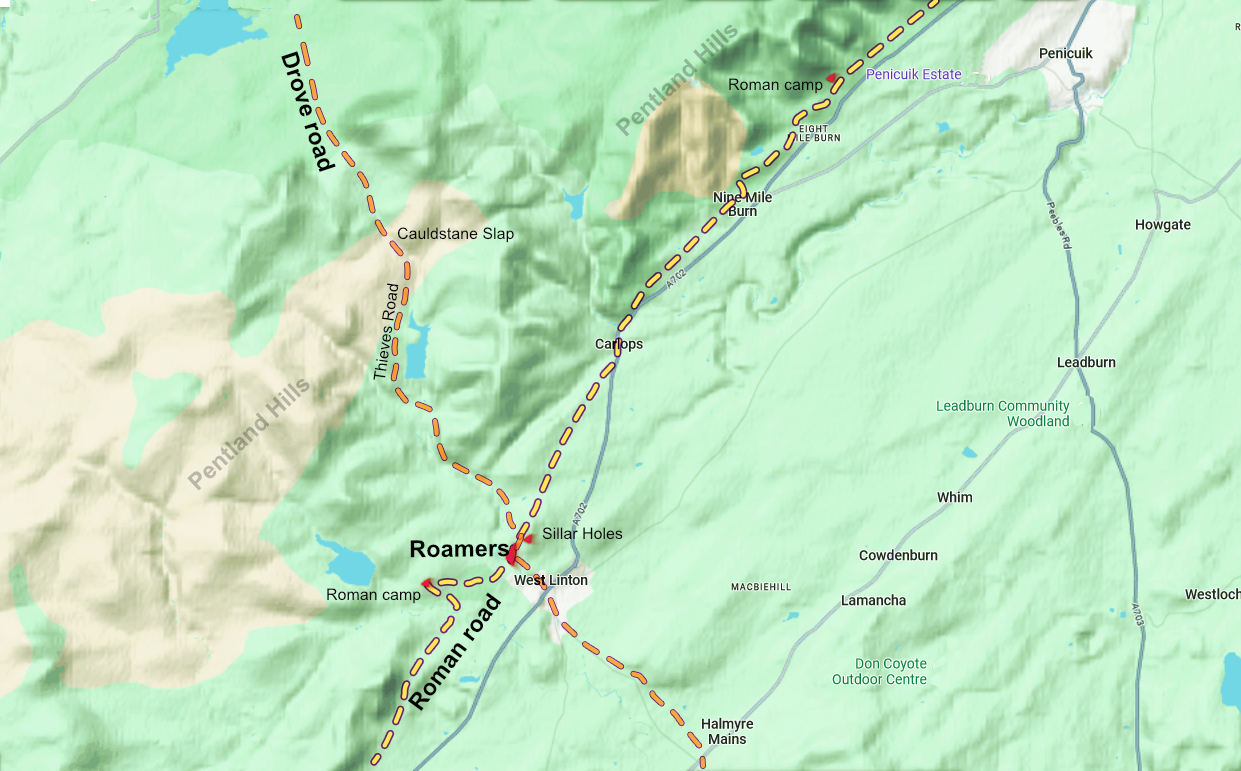

Roamers Wood has been at the centre of three historically important routes for travel and communication, with evidence still visible of its Roman Road, its nearby Sillar Holes and the Drove Roads, not to mention access to the famed 'Lintoun Mairket' more recently in its long history.

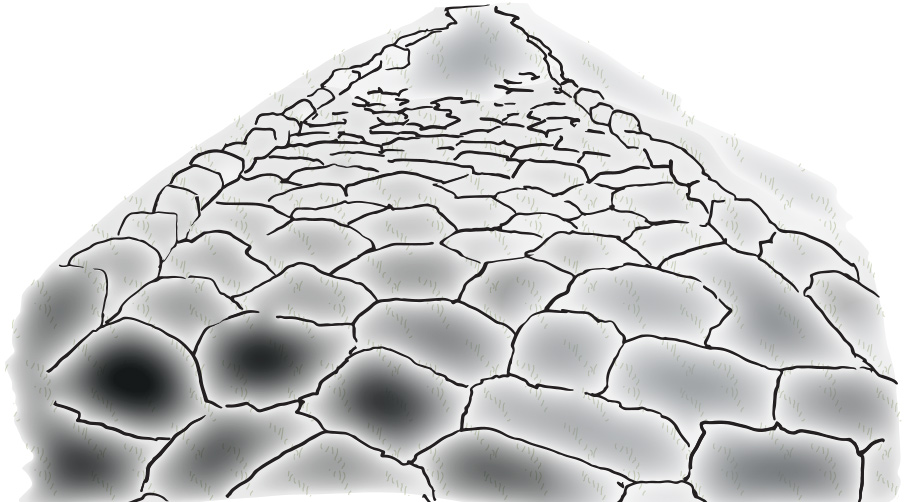

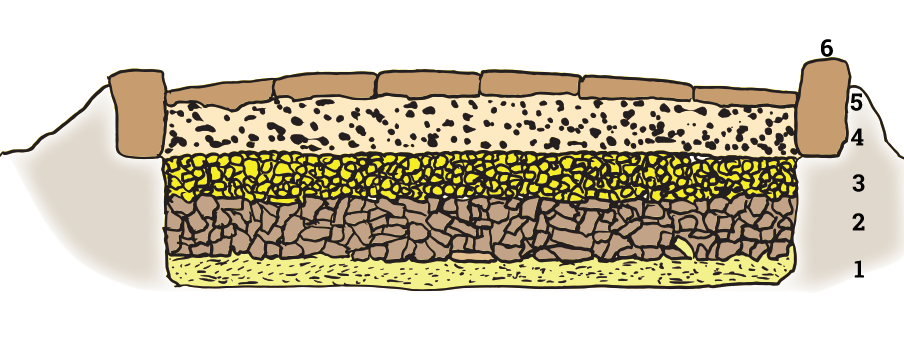

A typical roman road will have several layers, generally of sand at the base (1), followed by (2) a 'statumen' of large semi-crushed rock, followed by (3) a 'rudus' of gravel (plus mortar sometimes), then cemented gravel (4), and finally the layer of large flatter stones on top (5)... a 'pavimentum' (6) of vertically placed curb stones to either side of the road pin the main road stones together as well as define the drainage channels. Here in Roamers these drainage channels to either side of the road appear to be very deep, suggesting either a lack of stone for construction or perhaps severe run off of water. Careful excavation by someone who knows exactly what they are looking at is the hopeful solution to this puzzle at some day in the future!

For several hundred years, drovers passed this way, often through Cauldstane Slap (likely translates as 'coiltean slap' or wooded pass) and along Thieves Road (self-explanatory!) before passing down the Loan. Interestingly 'the Loan' derives from 'loaning' or borrowing, a very ancient tradition that still persists today since no one actually 'owns' the Loan, not even the Council.

Mary of Guise, mother of Jamie the Saxt, (sixth of Scotland, first of Britain) once financed her army through what happened half a mile further along the Roman Road at the Sillar Holes in around 1540. At that time, lead ore was often used as a means to create silver through a heating process (cupellation) and, whilst the latter was done abroad, the lead itself came from here, whose 'silver' was obtained through what are called 'bell pits' (a series of bell shaped pits, whose chambers linked through either ladders or a simple windlass). Early leather shoes found here and other objects from these mines are now in Edinburgh Museum...

Connecting memory to time through tree letters that define the yearly cycle plays a key role here. Each of its thirteen consonants corresponds to a 28 day sidereal, or lunar period that follow an anti-clockwise direction, while the five vowels follow a solar (sun-wise) direction to track solstice and equinox points. In addition, one hidden letter tracks the nineteen year metonic point when solar and lunar cycles re-calibrate in a lunar standstill (more on all this in the tree alphabet)

calendar

calendar

tree

fests

tree

fests

art

avenue

art

avenue

witches

plants

witches

plants