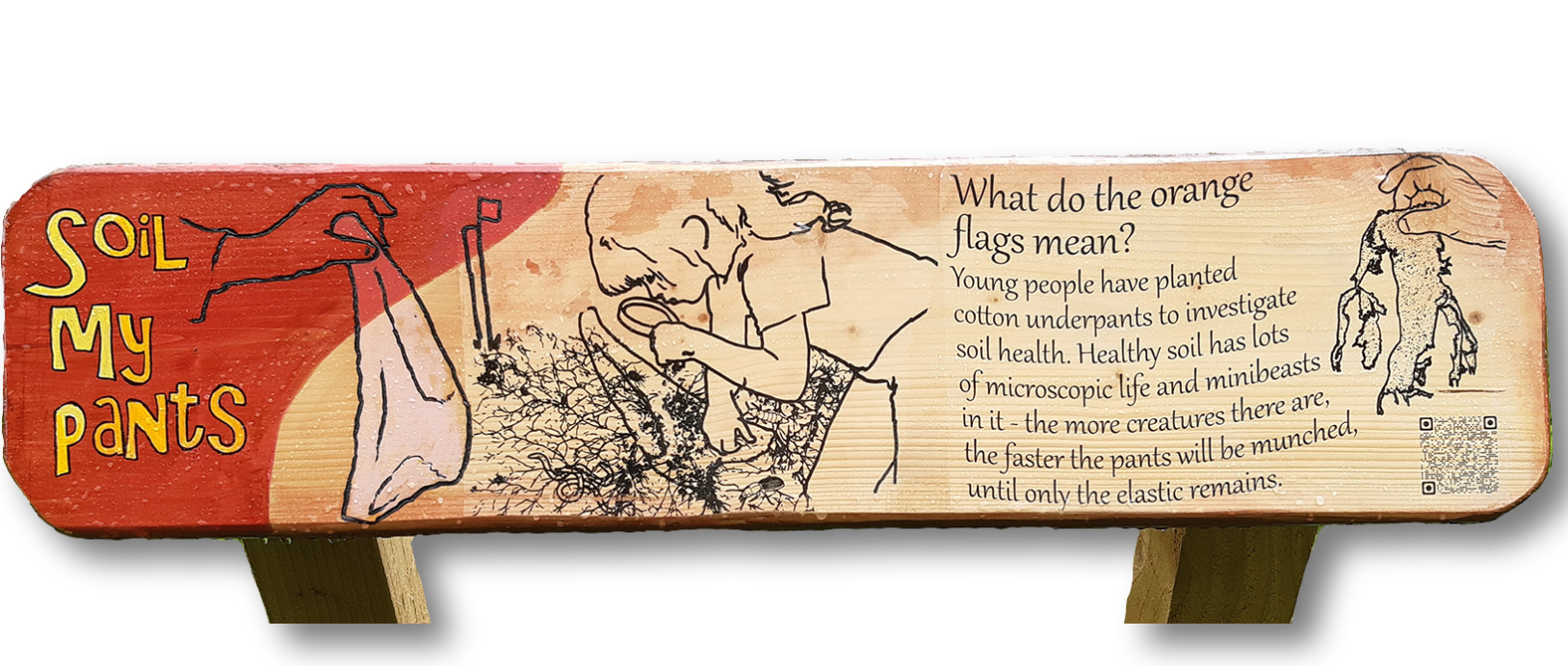

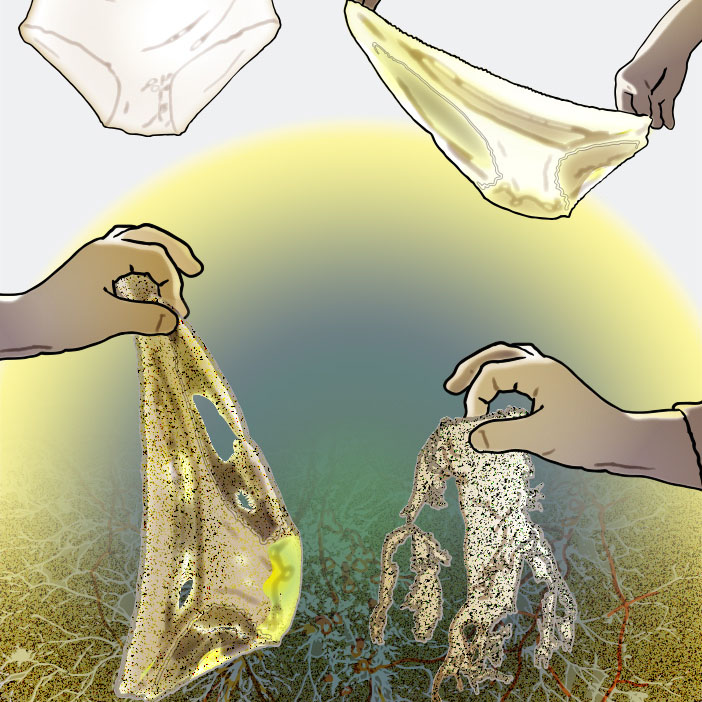

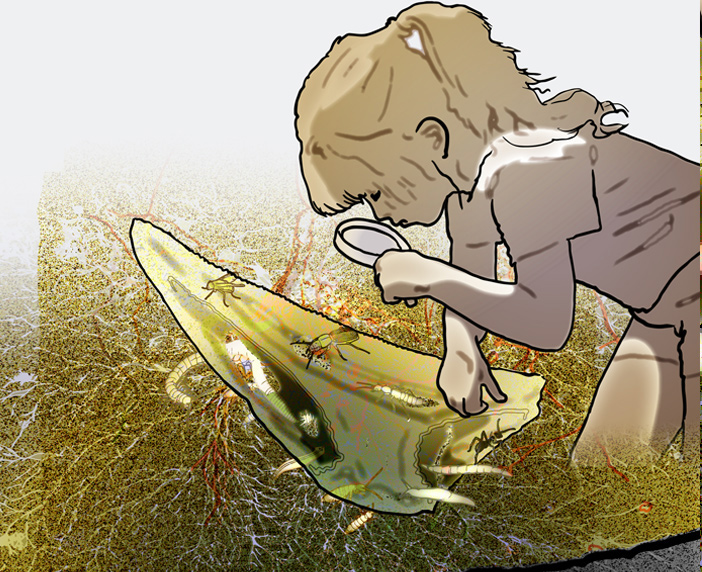

Working with pupils at West Linton Primary School and the West Linton Scouts, we have planted cotton underpants to do an experiment. Microscopic life and minibeasts that live in healthy soil eat the cotton in the underpants, creating holes. Every so often, we dig up the pants to take a look at how many holes have appeared. The more creatures there are, the healthier the soil, and the faster the cotton in the pants will be eaten until only the elastic remains.

We think that the soil at Roamers will become healthier over time which means there will be more different kinds of soil creatures to munch through the underpants faster and faster. In a healthy woodland with warm soil that is not too wet, it takes 2-3 months for underpants to be eaten up. In turn, soil microbes and minibeasts help trees stay healthy and grow by providing the right types and levels of nutrients needed by trees

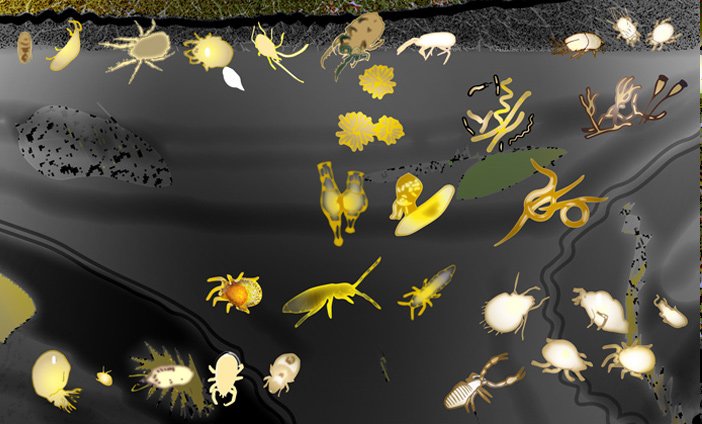

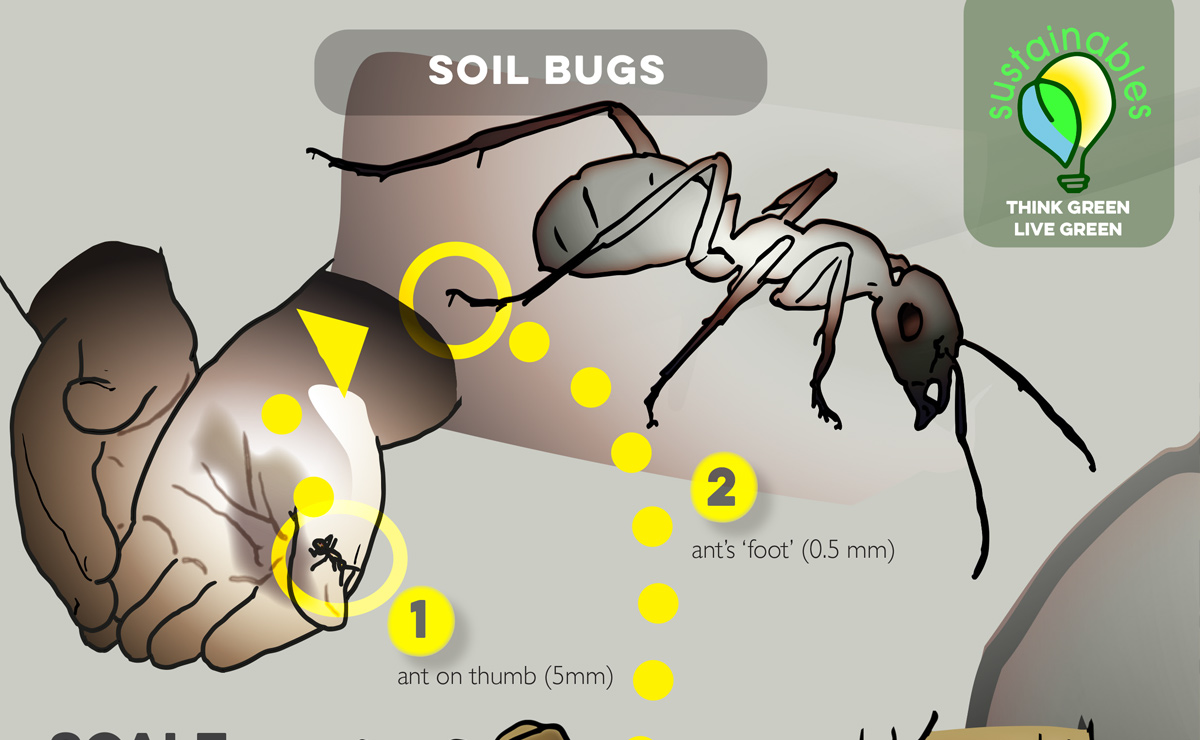

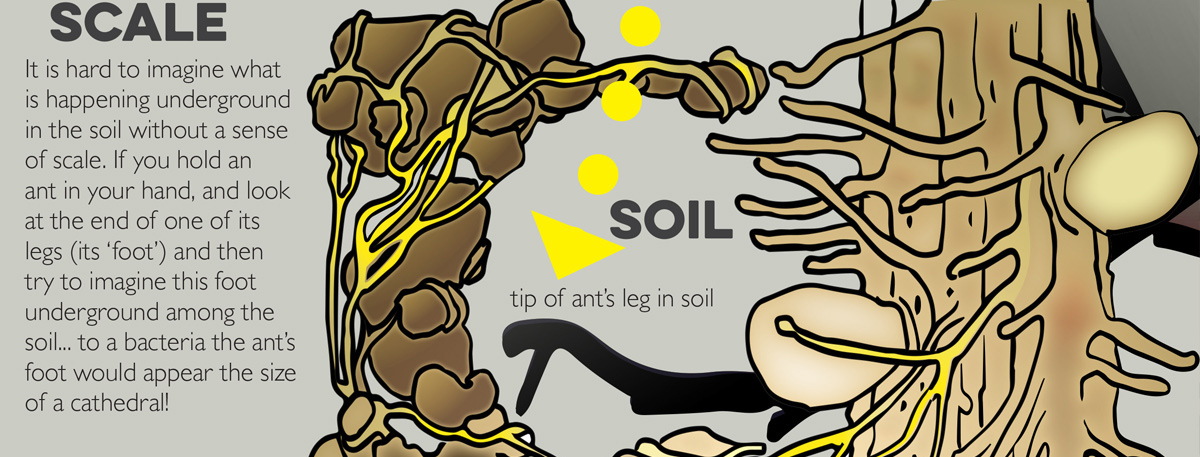

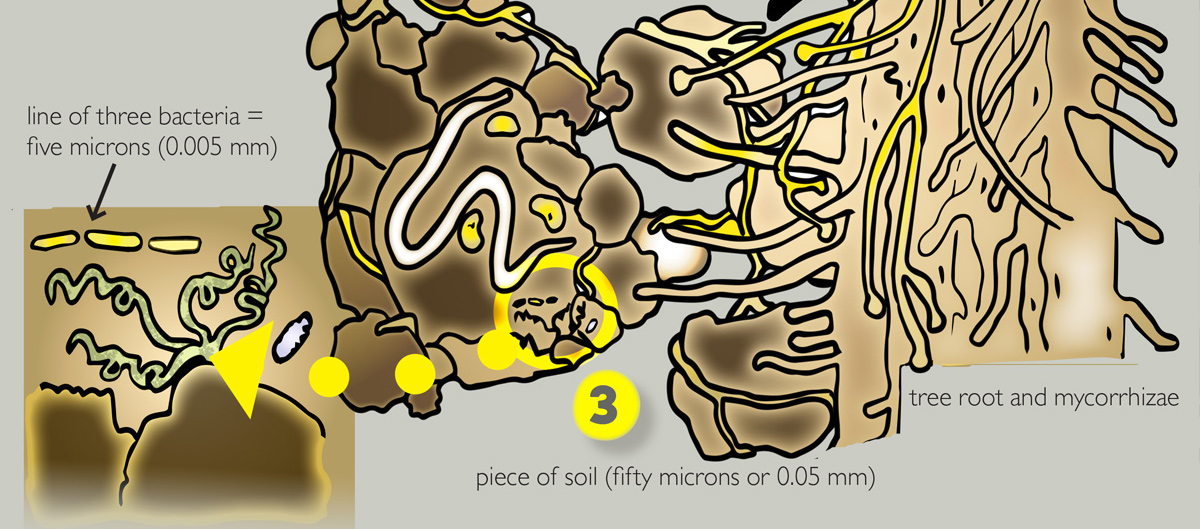

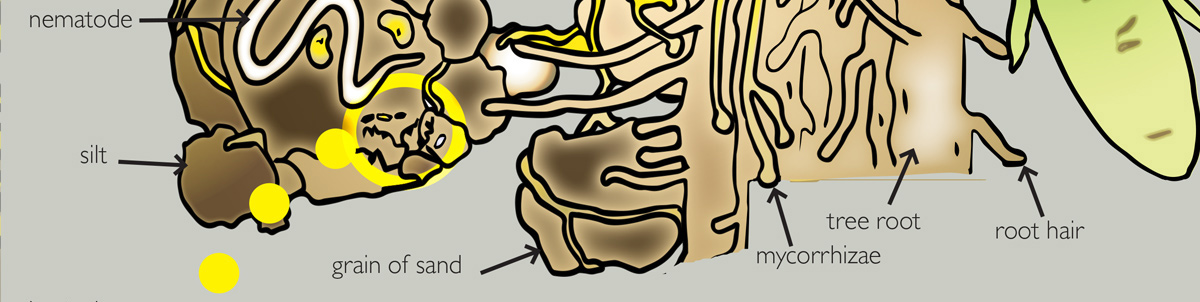

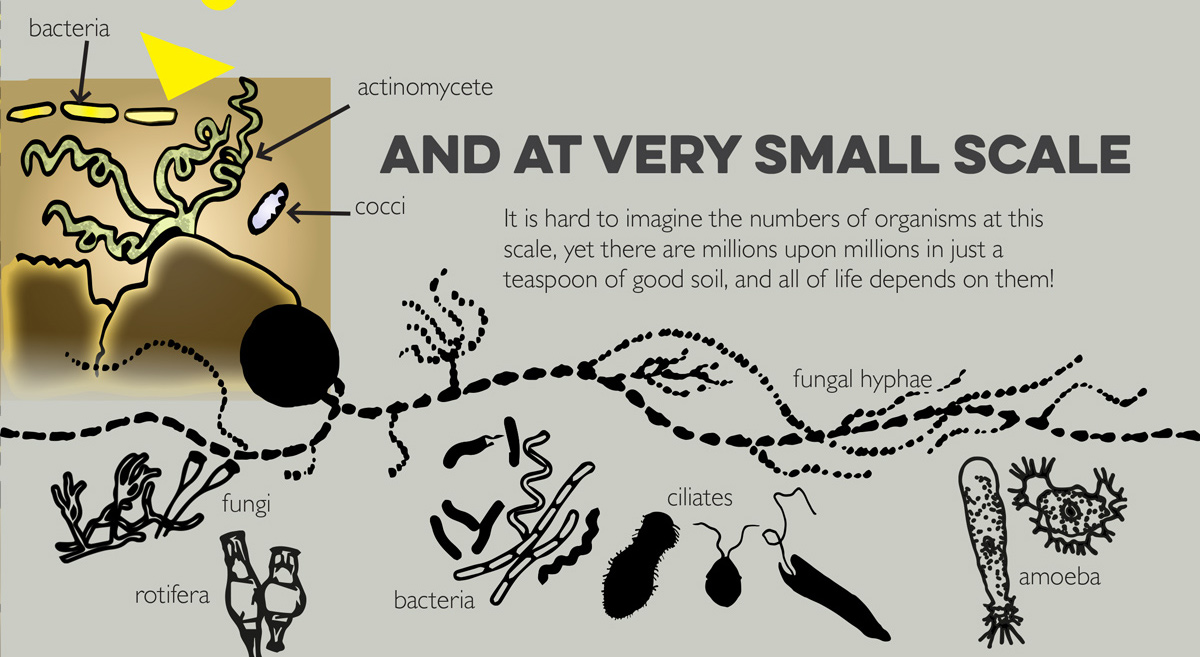

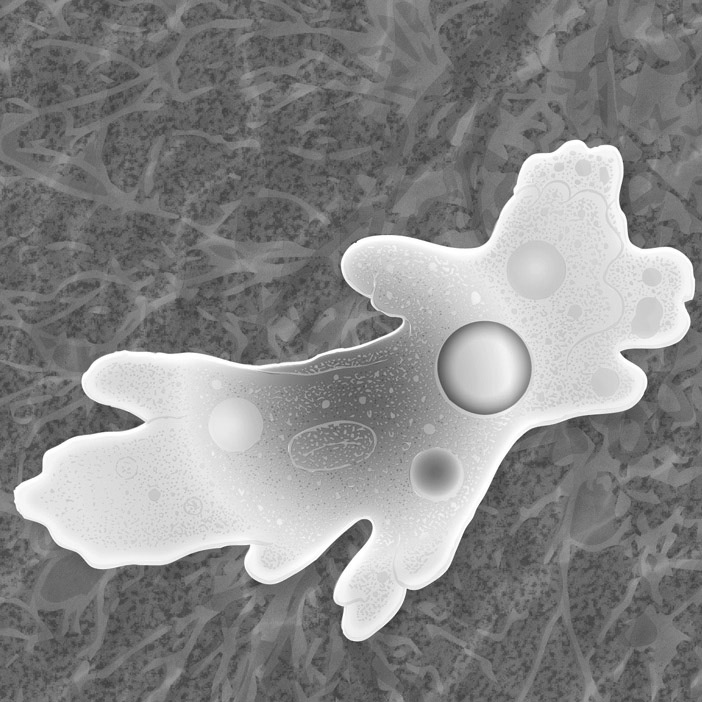

Soil is much more than just mud! Soil is home to vast numbers of microorganisms – tiny creatures too small to see unless you look at them through a microscope. In just one small teaspoon of soil, there are over 1 billion microbes! Microbes living in the soil play an important role in making sure plants get the right types and levels of nutrients which keep plants healthy and enable them to grow. In return, plants provide homes and food sources to the microbes, so everyone benefits from this interactive community!

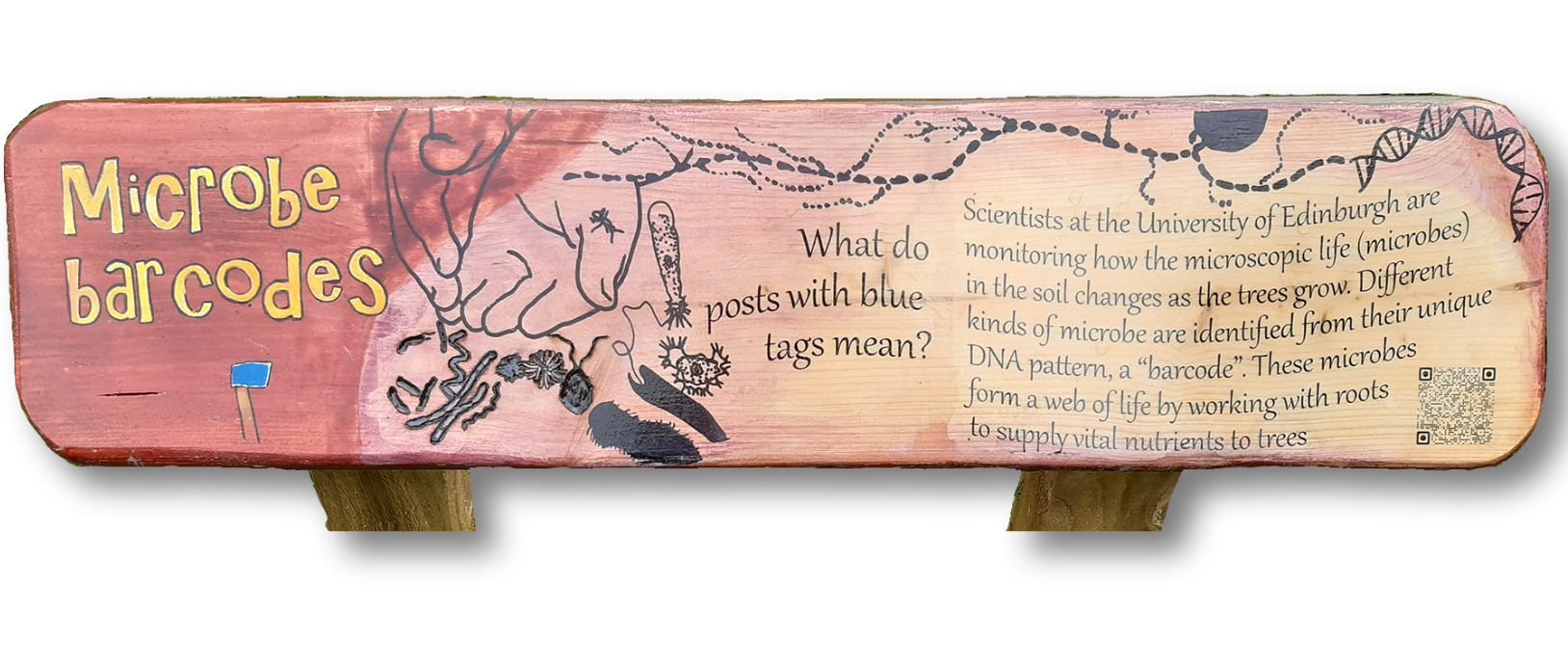

Every month Scientists are digging out small samples of soil and freeze drying them to preserve the DNA of the microscopic life. Scientists extract the DNA using a chemical reaction and send the DNA for sequencing to read the DNA code. The sequences can be used, a bit like bar codes, to identify the different species of bacteria and fungi in each sample. We think that as different types of trees and shrubs grow, their leaves will provide a rich layer of food on the ground, leading to a more varied range of microbes in the soil samples.

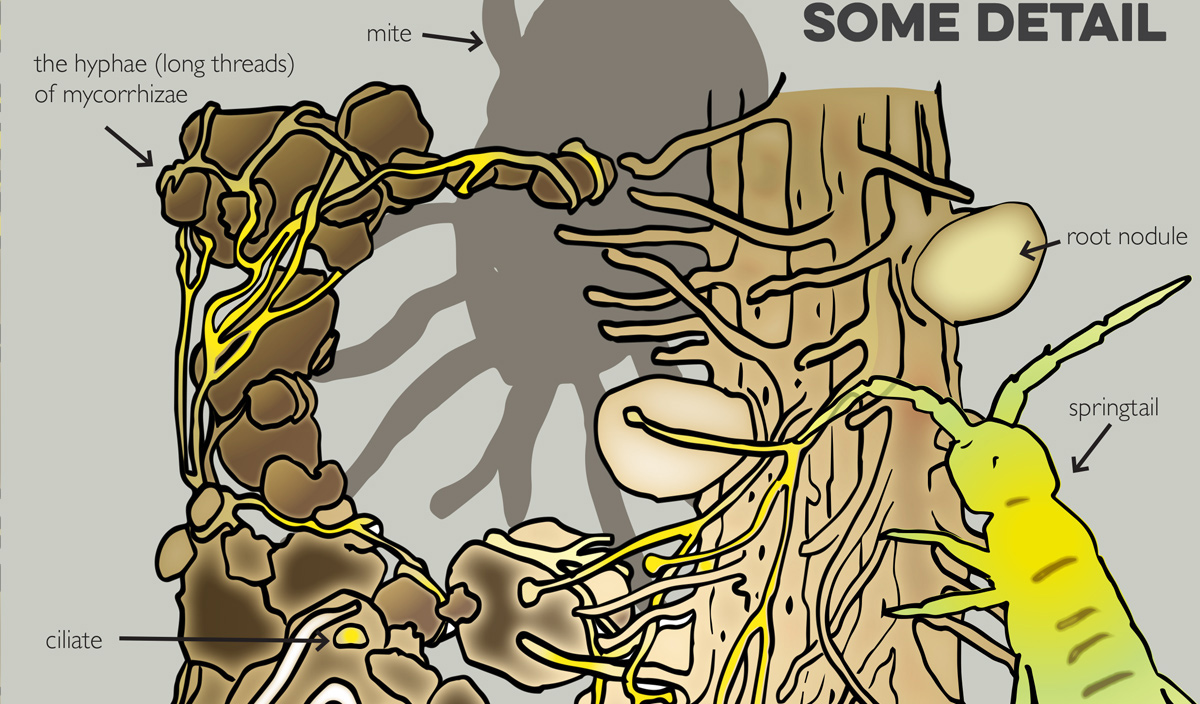

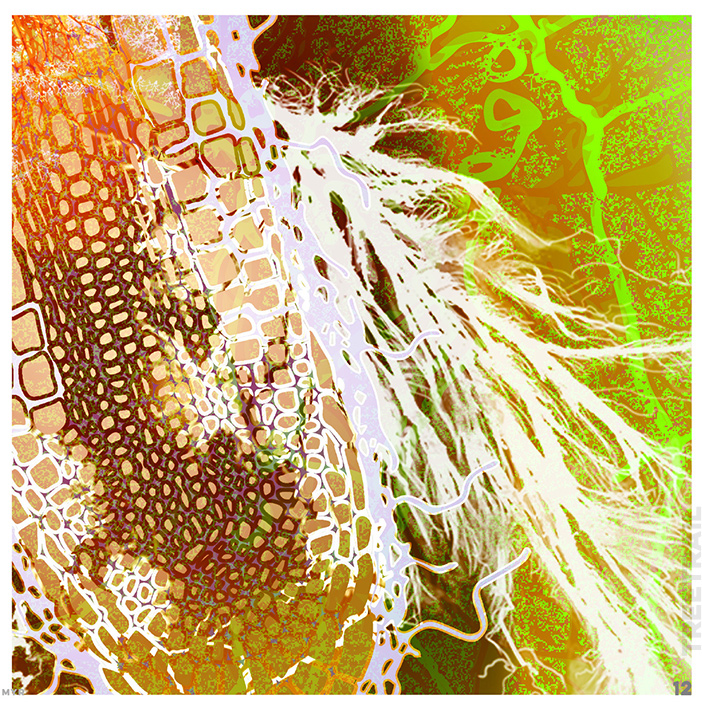

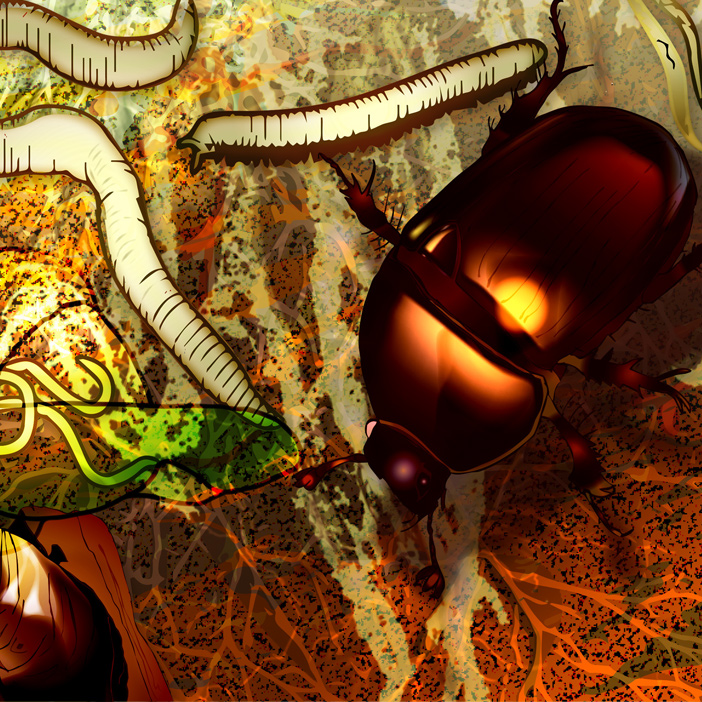

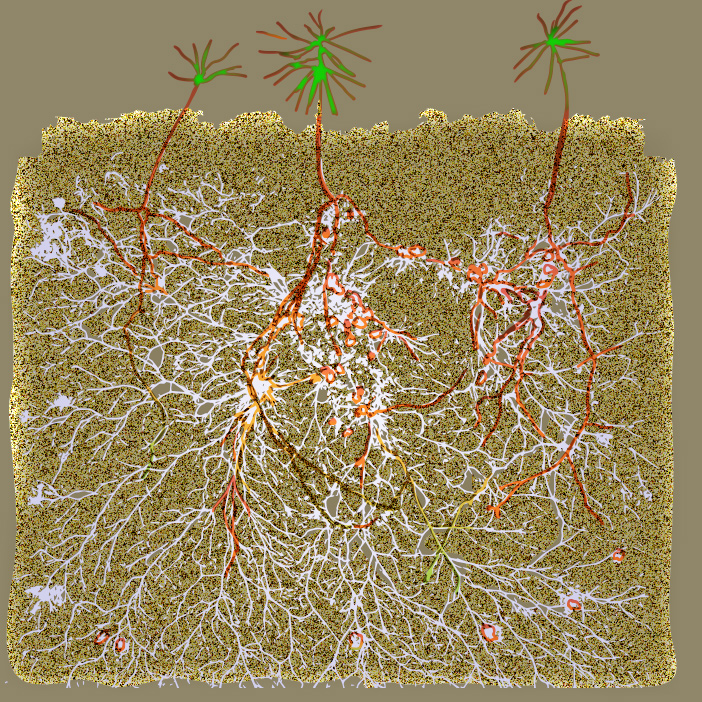

Some microbes can transform locked away chemicals like nitrogen in the air into a different form of nitrogen that can help plants to grow. There are different kinds of microbes that can process different nutrients to make sure there is not too much or too little available to plants. For instance, fungi (of which mycorrhizae are a major part) can grow long tendrils (called hyphae) through the soil which transport nutrients to the roots from further away. The result is that plants can access nutrients from sources that they simply would never be able to reach otherwise.

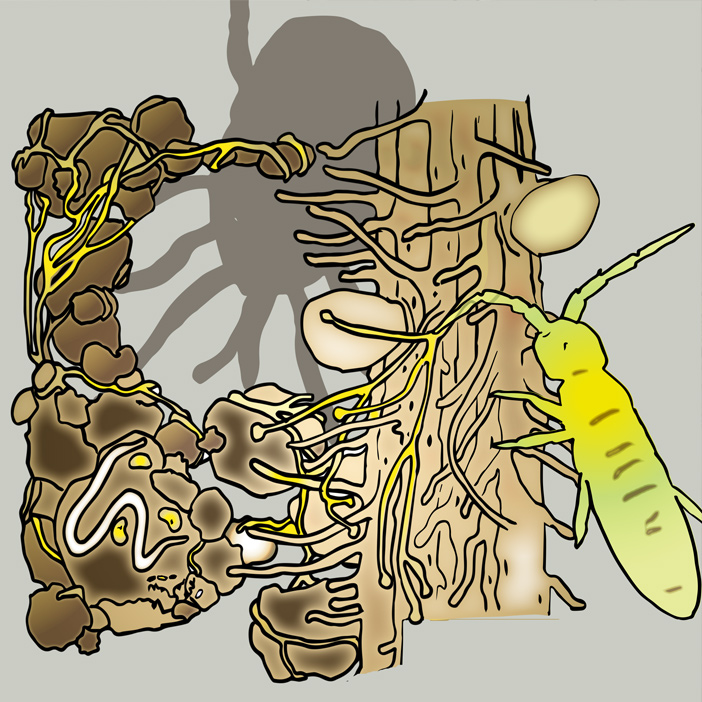

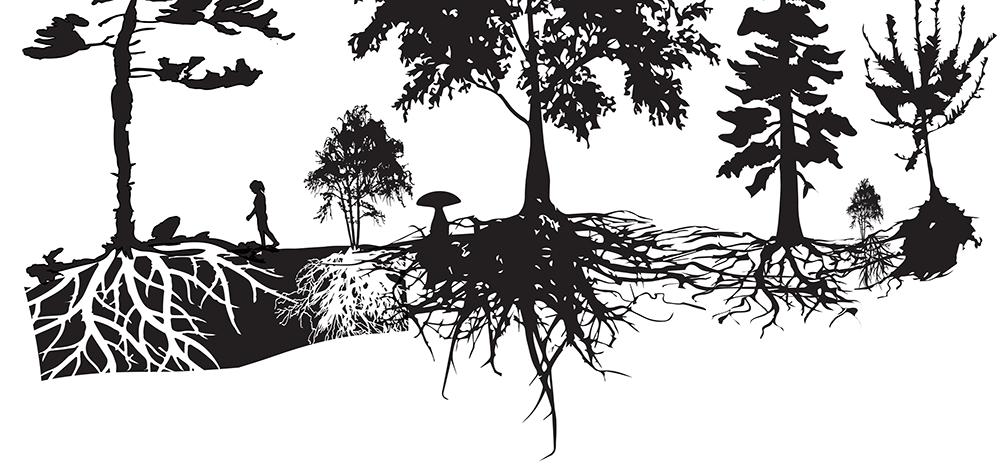

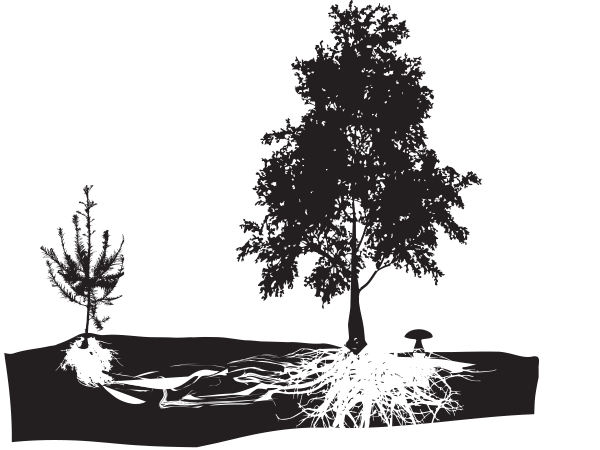

A bit like a needle and thread, underground are countless mycorrizhae that weave between everything.

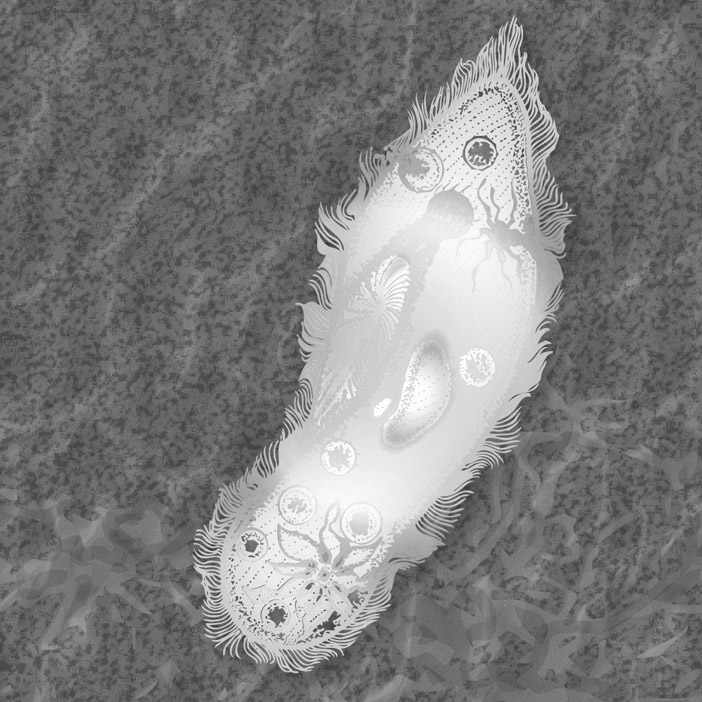

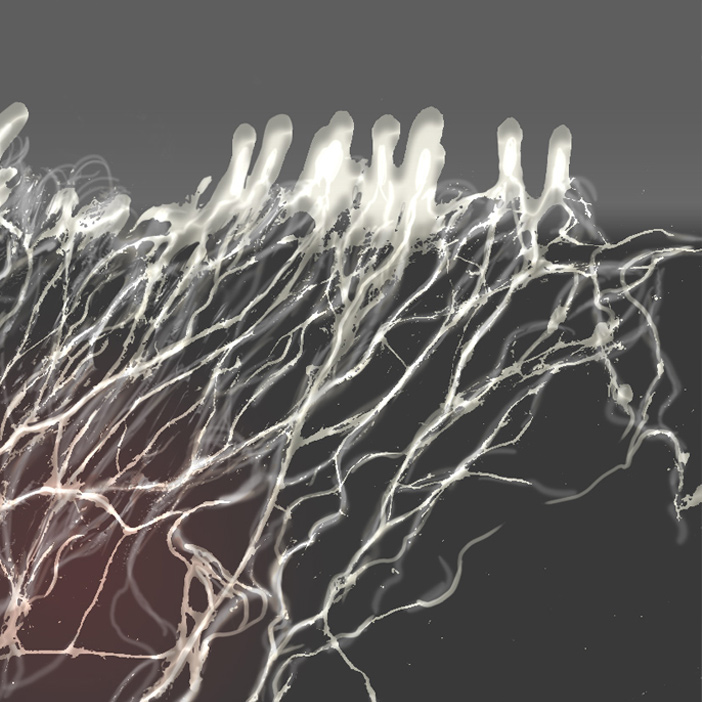

Mycorrizhae ('mykos' for fungus and 'rhiza' for root) are almost too small to see, until lots of them create a visible cloudy effect.

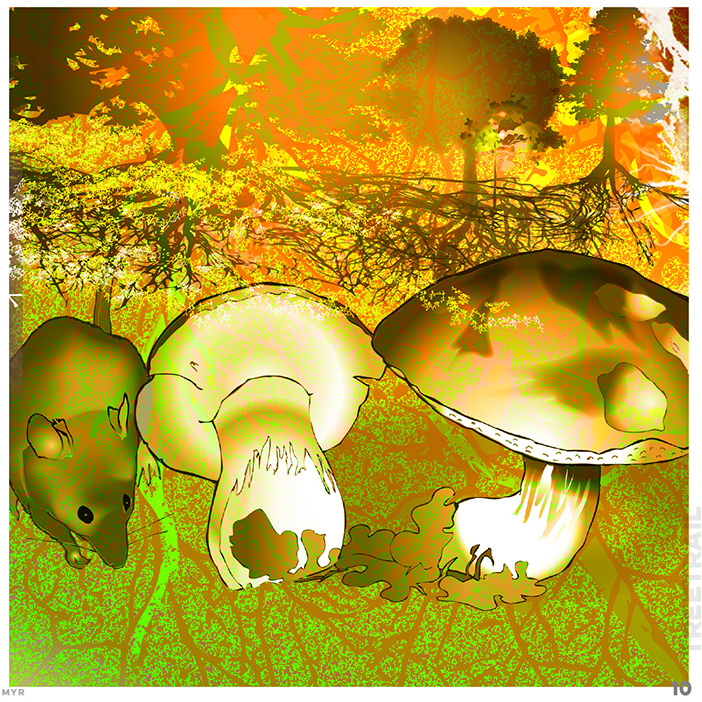

They connect to everything that grows, and mushrooms are strictly speaking fungal 'fruit'.

They also connect right into tree roots (see how their white threads grow inside this root tip).

And these threads spread out through the soil collecting water and minerals for the tree in return for the its sap.

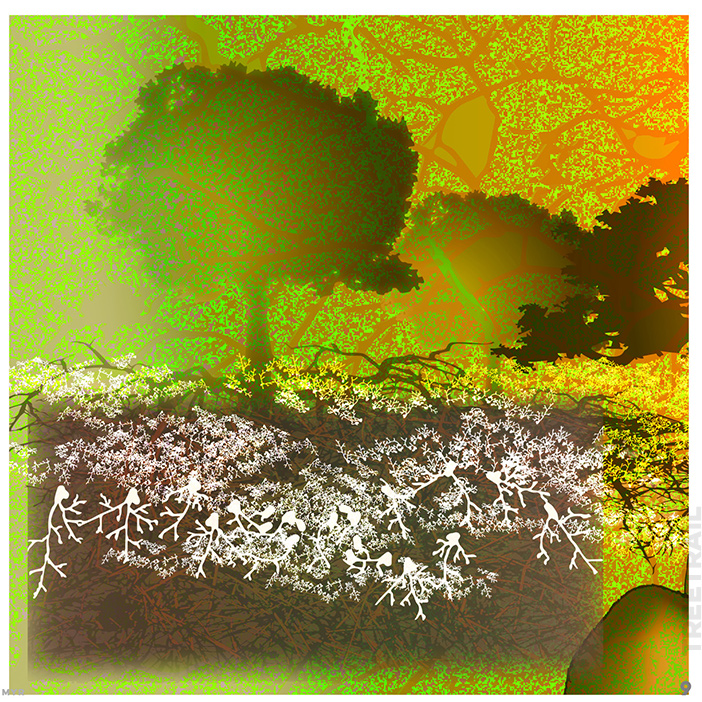

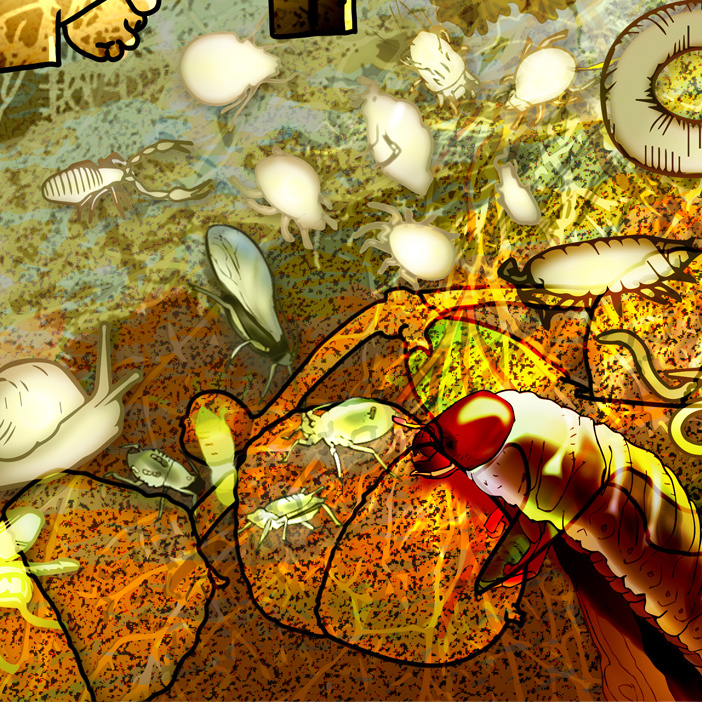

And near the surface, as leaves and twigs decay, tiny organisms feast on continuous decomposition.

The fungi, bacteria and bugs all break down dead material into all forms of new foods.

This underworld foodchain allows nutrients to be picked up by plants of every kind as well as support all kinds of insects.

So whether a gnat, a flatworm or an oak seedling, all depend on this regeneration process in their own ways.

And when you make a bug hotel, then imagine how you help this vast city of hidden life!

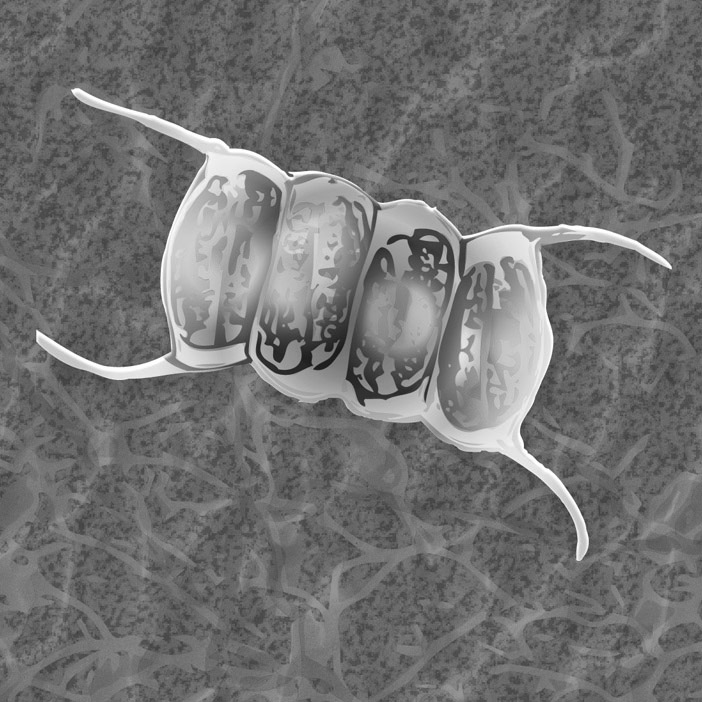

Fungi can grow long tendrils (called hyphae) through the soil which can interact with plant roots and transport nutrients to the plant from further away. This means that plants can get nutrients from sources that they could not reach otherwise. Trees may even communicate with each other through the networks that fungi make in the soil.

Sometimes called the wood wide web, tree ‘talk’ forms a communication along which vital nutrients and signals are traded through the hidden underworld of messenger fungi, or mycorrhizae, whose trails (the hyphae) may extend across vast distances.

Below ground lies a network of symbiosis, or cooperation, allowing trees to connect and grow using mycorrhizae.

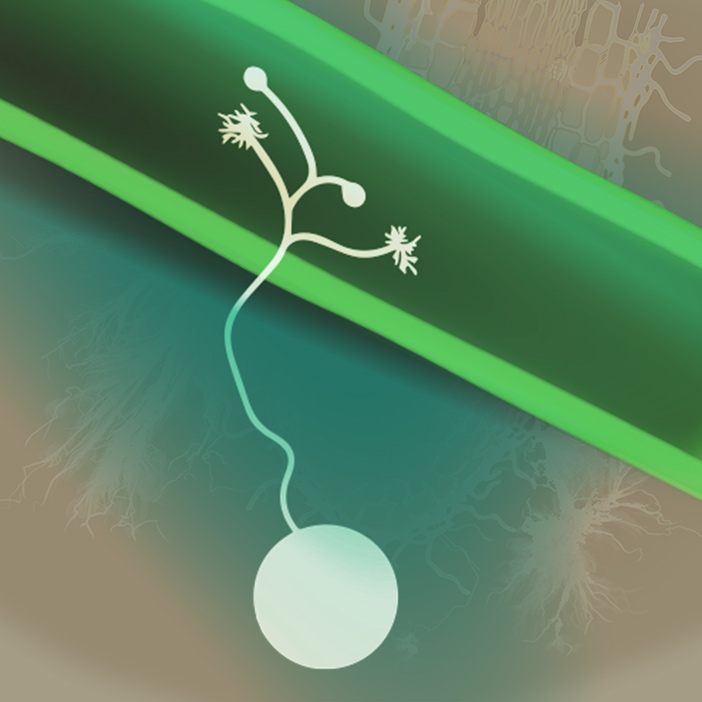

Mycorrhizae are a form of fungus, that helps growing trees to absorb water, phosphorus and carbons in exchange for a share of the sugars the tree makes in in its leaves.

Through the mycorrhizae, minerals and chemicals travel and alerts about dangers can also be sent.

Even when fully matured, this tree- fungus symbiosis remains, with some trees becoming 'mother trees’ by extending the network to others.

Mycorrhizae (white) can form incredibly long interconnected chain of threads with tree roots (orange) across woodlands of several miles.

A single mycorrhiza fits between the walls of neighbouring cell walls in a tree root.

The pale threads of mycorrhizae surround both the tip of the root as well as entering the interior between the cell walls, allow two-way exchange to take place.

Although there are thousands of different species of mycorrhizae that connect to many another types of plant, all have long filaments (hydrae) that grow fast.

Here are some of the fungi that grow in Roamers Wood, at different times of year and in different places

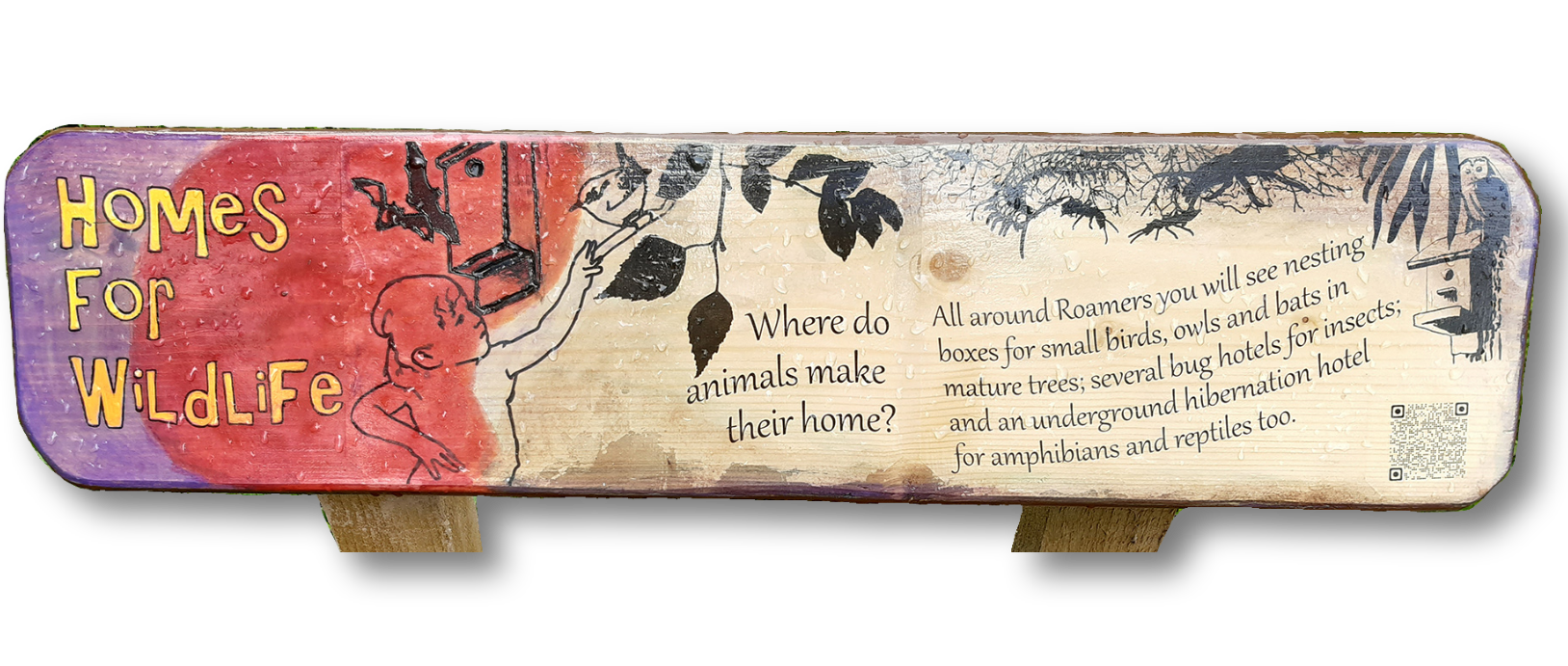

Creating homes for wildlife to thrive is a vital part of restoring a woodland habitat. With help from the pupils at West Linton Primary School, Roamers Wood has several bug hotels with fabulous names, including “Buggingham Palace” and “Be a Bee in a Bee B’n’B” for insects and other mini beasts to live. Pupils have also constructed underground homes for amphibians and reptiles to hibernate in, called “hibernacula”. The bird boxes are different sizes, some suitable for small birds and others for tawny owls, and special boxes welcome bats to roost and hibernate. Every spring we make pet fur, tumble dryer fluff, and grasses available for birds to collect to line their nests. Look out for a pine marten nesting box that will be coming soon.

The bug hotels are stacked pallets filled with grass, leaves, and pinecones to provide dry hiding places, and pipes and special bee bricks, made by pupils, provide hollow tubes for solitary bees to make their nests. Like their relatives, honeybees and bumblebees, solitary bees are important but overlooked pollinators. There are more than 100 species of solitary bee in the UK and instead of living in a hive, each female bee makes a series of chambers in a hole or hollow, putting an egg and some pollen into each chamber before sealing it up with cut out sections from leaves or flowers, or mud that they gather. When the eggs hatch, they eat the pollen, eventually becoming an adult bee the following spring that breaks out of its nesting chamber to continue its life-cycle.

Shavings provide useful material for lining a bug house

Hair and mosses are good lining material for many nesting creatures

Each hibernaculum is nearly half a metre deep and filled with pipes, sticks, leaves and rocks, to provide safe nooks and crannies for newts, frogs, toads, and snakes to spend the winter safely. Scotland has one species of frog, the common frog, two species of toad, and three species of newt. We have already seen toads and frogs in Roamers Wood, and it is likely there are smooth or palmate newts around too. Common frogs can differ a surprising amount in colour, from brownish to greenish and even red, but they are all the same species. Frogs jump whereas toads crawl, and frogs and have smoother skin than toads. The skin of all amphibians is easily damaged by the dryness of human skin, so it is best not to pick them up. Sometimes, male frogs and toads spend the winter in a pond, but females overwinter on land, we hope they find the hibernacula.

| Species | Preferred place | Time of year | Why they like it | Benefits |

| regular shaped tubes | spring and summer | eggs | pollinate flowers | |

| bits of wood | winter | hibernation | control aphids | |

lacewings |

tubes and passageways | winter | hibernate and shelter | eat pests (aphids and greenflies) |

other bugs |

corners and crevices | all the year | shelter and hibernation | food chain conservation |

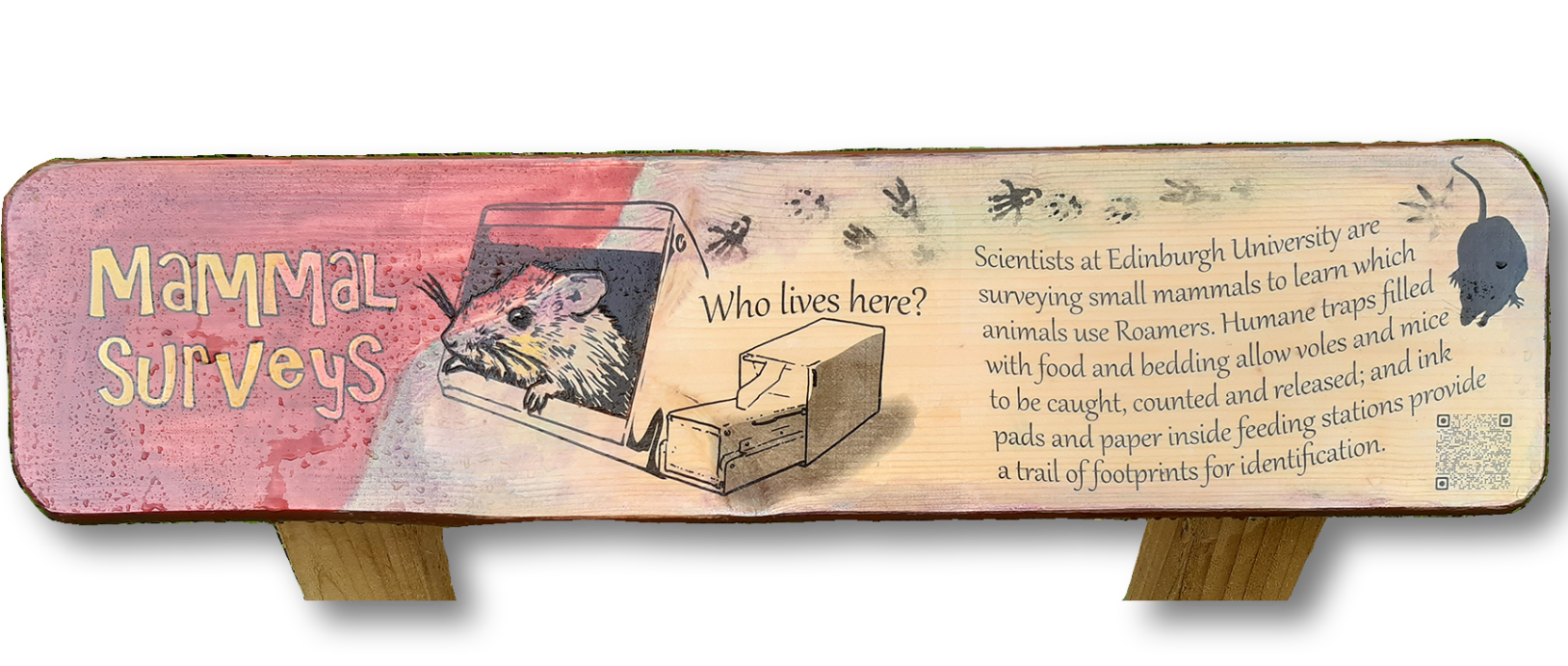

Like most of Scotland, Roamers Wood is home to wood mice and field voles. University students are surveying how the numbers of these small rodents change as Roamers Wood develops. Both wood mice and field voles can temporarily be caught in special traps, called Longworth Traps. Each trap has a small hole so that shrews, who are scarce in the UK, can leave when they wish. When a wood mouse or field vole is caught, a tiny patch of its fur is clipped off so that it is not counted if captured again.

Opening a trap in a plastic bag to check who might be hiding inside.

Longworth trap .

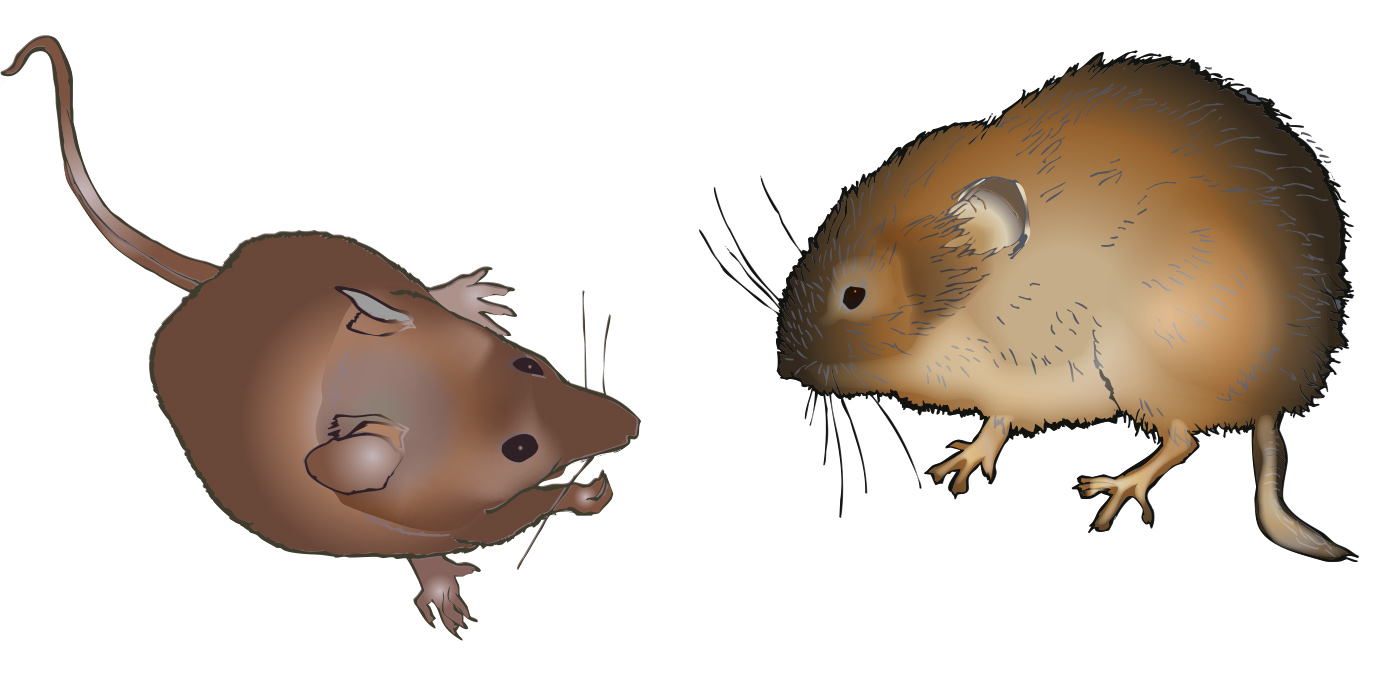

Field voles and wood mice are similar in size to house mice, but can be separated by looking at their faces, tails, and colour. Field voles are generally grey-brown, with a round face, and short tail, whereas wood mice are chestnut-brown, with large ears, and have a tail as long as their body. Wood mice are nocturnal, sleeping in the daytime, but field voles live a speeded-up life because they sleep, eat, roam around, in cycles that last 2-3 hours.

Long grass provides excellent cover for field voles and wood mice to roam unseen, plenty of seeds for the winter, and they will also enjoy the fruits of Berry Lane and Robert’s Orchard in the future. Field voles and wood mice also play an important role in dispersing seeds from plants and trees around woodlands. So, we expect that as the woodland develops, more and more small mammals will make Roamers Wood their home. If field voles and wood mice have enough food, they can breed as often as six times in a year! Even though very few live longer than one year, their fast-breeding means there are about as many field voles as people in the UK!